A reader writes:

A Foghorn post I read today talks about reading mirages in long range rifle. I’ve wanted to know more about how to do that ever since I learned it was something people did, but since I never get to spend any time on a range larger than, say, 100 yds, and certainly never with people that actually know what they’re doing, all I’ve got to learn from is what I read. So I wanna read more 🙂 How do you read mirage? At different distances? In different weather conditions? kthxbye…

Why do you guys never ask easy questions? Oh well, here we go…

Our question today can really be broken down into two parts: what is a mirage, and how does it factor into shooting.

A mirage is not a hallucination, as Wikipedia is quick to make clear. A mirage is a naturally occurring optical phenomenon that we encounter every day. Mirages occur whenever you are looking at a distant object over a hot surface, such as the ground or a stretch of road after the sun has been baking it for a while.

The warmth of that surface heats the air above it which mixes with the cooler surrounding air and causes the light to bend or “refract,” creating a wavy pattern that blurs the distant object.

The key thing to remember here is it’s the mixture of hot and cold air creating the issues, not just the hot surface of the ground.

Just like in the picture above (yep, you guessed it, shamelessly stolen from Wikipedia), the further away the object is from the observer, the more blurry it is. That’s because mirage is a cumulative effect; the more air the light has to pass through to get to your eye, the worse the mirage will be.

As you can see with the straw in the water glass pictured above (Wikipedia is GREAT for images…), that bending or refraction of the light means that the image you see doesn’t necessarily correspond with the real position of the straw. The water creates a “virtual image” of the straw that appears in a different position than the actual straw would be.

The cumulative effect of a mirage means that at shorter distances it doesn’t really matter for shooters. At 50 yards a mirage is probably not going to throw your shot very far off. But at longer distances, say 200 yards to infinity, the further you go the more the mirage matters, and the further the “virtual image” will appear from the actual target.

Imagine setting a large target 1,000 yards from your firing position across a blacktop surface. Now imagine you have a scoped rifle of some sort. If you look down the scope with the crosshairs on the target, on a warm sunny day that target will be bouncing all around without you even touching the rifle.

In the above image taken at 200 yards last weekend (when I was participating in the Bridgeville High Power 800 Agg competition with the ArmaLite M-15 A2 National Match Rifle) you can already start to see the the target deforming due to the mirage, losing its nice and round shape. At 600 yards it looked like I was peering through a whirlpool at the target.

Under these kinds of conditions, the shooter needs to stop and think really hard about what they’re doing. If they line up the crosshairs with the bull’s-eye as normal, their shot is probably going to end up missing because they’re shooting at the “virtual image” instead of the actual location of the target.

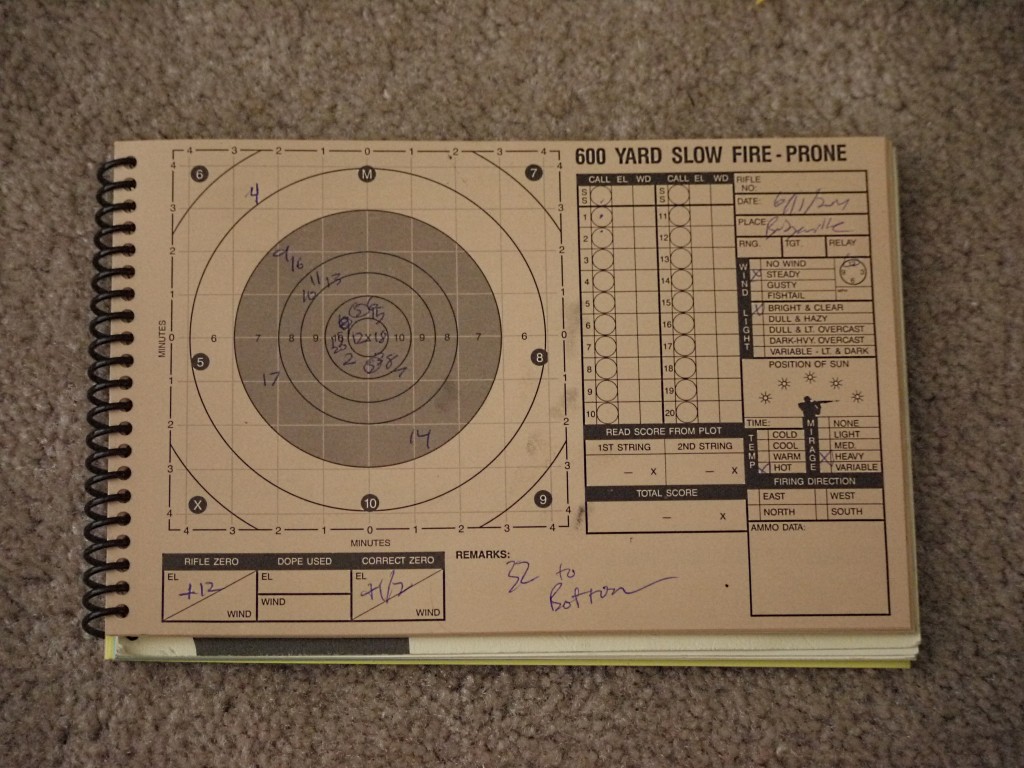

The key concept to take away from today’s “Ask Foghorn” is that when there’s a mirage in play you need to stop trusting the image of the target you see in your scope or behind your crosshairs, and the logbook entry above is the perfect example.

I was nailing the 600 yard shots, but when the wind shifted I started dropping points. Even taking into account the lazy three M.P.H. wind (which I compensated for with 1 MoA windage and shouldn’t have factored into the issue much), I was still consistently about a foot off the X ring. This drift was due to my lack of experience in reading the mirage and shooting for the “virtual” target instead of the “real” target.

So just how do you compensate for this mirage? It takes a lot of practice, experience and time on the rage—just like most things in the shooting sports.

In general, mirages will tend to appear to move in the direction of the wind. That’s relatively easy to predict with a straight crosswind, but a bit harder when the wind is coming in at an angle. Also remember that the mirage is a cumulative effect, which means that you have to account for the direction of the wind all the way down the range and not just at the target.

When there’s no wind the target may appear to “boil,” as it does with the target above. Mirages can move the image of the target both up and down as well as left and right, but where the target will actually be when these conditions are present depends a lot on the weather conditions of the day and the characteristics of the range you’re sitting on.

In short, the best way to read a mirage is by trial and error. There’s no surefire mirage reading technique I’ve come across yet in my research, but if I find one I’ll be sure to pass it along. Just remember the basics and give it a guess.

TL;DR: Mirages appear to change the position of the target, and no one has any concrete methods to read the mirage. Experiment with it at your own range to get a feel for it.

For more information:

If you have a topic you want to see covered in a future “Ask Foghorn” segment, email [email protected].

One tip is to focus the spotting scope short of the target, i.e. focus the scope on the mirage rather than the target so the mirage waves can be more clearly seen.

I generally take the wussy way out. I try to look for the dominant mirage and wind condition, and get my sighters off during that condition. I try to only shoot when I see that same mirage and wind condition, even if it means sitting around for a few minutes. Sometimes this means waiting for the wind to die! I’ll get off shots quickly during the conditions I sighted for. I just don’t have enough experience making wind corrections on-the-fly to adjust during a string effectively. So far, I have not ever run out of time, but have gotten off my 20th shot in the 19th minute. Slowly but surely I’m going to be brave and adjust for conditions during a string!

I bought a little digital wind meter to take on walks, every now and then when the breeze picks up I try and guess the strength of the wind. My wife thinks I’m crazy…

Reading this makes me appreciate the skill of our marksmen in Iraq and Afghanistan. How they hit anything (not to mention a man sized man) at the ranges that they do is nothing short of miraculous.

I may be wrong about this, but my initial guess is that the mirraged-image will shift in relation to the actual-image depending on the location of the sun (i.e. time of day) or other light source. Looks like I’ll need to get out my old physics textbook and catch up on some reading…

The scientific term for what shooters call “mirage” is terrestrial scintillation, which might paint a clearer picture of what it is and how it affects long-range vision through a liquid medium such as air. You can use mirage to dope the wind and vice versa. To practice studying their effects when you’re not at the range, pick out a scene in the distance with fixed horizontal elements (such as man-made structures) to read the mirage, and non-fixed vertical elements (trees and grass) to read the wind. By comparing the appearance of the horizontal vs. vertical elements, you can gauge the wind and mirage in the scene. Some shooters carry a Kestrel with them whenever they go outdoors to practice doping the wind and mirage.

You can also practice looking at things at long distances while driving, which is not a bad safety practice either. Drivers tend to fix their stares somewhere just in front of their hood ornaments, when it doesn’t hurt at all to know what’s happening a half-mile or a mile down the road.

I say shoot until he falls over. Problem solved. No, it really gives you appreciation for the skill of a long distance sniper.

Comments are closed.