Perhaps no other American president was a better embodiment of the people he represented than Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt was a tough self-made man who ran a Dakota cattle ranch during the days of the Wild West. He was bellicose speaker and notorious hunter. But there was more to the man than a cartoon persona of burly weight-lifter’s physique, walrus mustache, and snapping choppers. He was an intellect without equal among his fellow office holders, with the possible exception of Thomas Jefferson. He is the only sitting president to have earned a Nobel Peace Prize. His public policies were nuanced and he was a tender-hearted husband and father. In Colonel Roosevelt, biographer Edmund Morris explores the final, often violent, years of the former president’s life.

Perhaps no other American president was a better embodiment of the people he represented than Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt was a tough self-made man who ran a Dakota cattle ranch during the days of the Wild West. He was bellicose speaker and notorious hunter. But there was more to the man than a cartoon persona of burly weight-lifter’s physique, walrus mustache, and snapping choppers. He was an intellect without equal among his fellow office holders, with the possible exception of Thomas Jefferson. He is the only sitting president to have earned a Nobel Peace Prize. His public policies were nuanced and he was a tender-hearted husband and father. In Colonel Roosevelt, biographer Edmund Morris explores the final, often violent, years of the former president’s life.

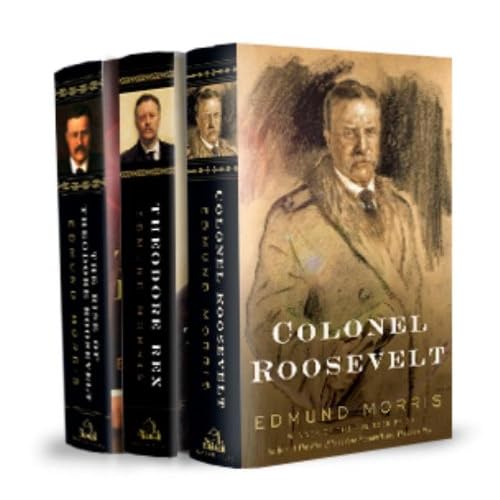

Edmund Morris began documenting Roosevelt’s remarkable life thirty years ago with his Pulitzer Prize winning The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, followed twenty-two years later by Theodore Rex. In the first book we read about a sickly boy who builds himself into a strong man, who suffers through the tragic death of his young wife, and emerges Vice President of the United States after gaining notoriety leading his “Rough Riders” volunteer cavalry regiment to victory over the Spanish in Cuba. In the second volume, Morris covers the assassination of President William McKinley and the seven and a half years of Roosevelt’s own dynamic presidency.

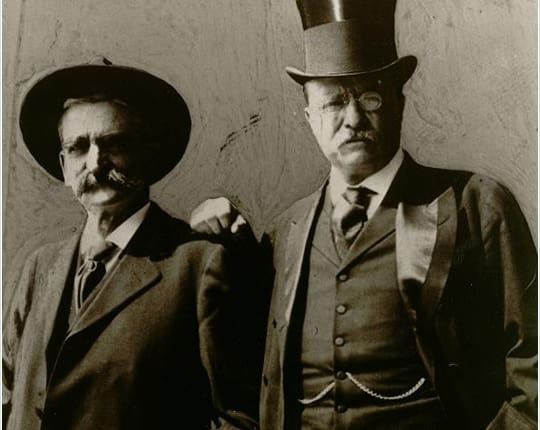

Colonel Roosevelt picks-up with the Colonel, the honorific Roosevelt preferred after leaving office, on safari in Africa on commission from the Smithsonian Institution to gather animal specimens for its natural history museum. The safari was co-sponsored by Roosevelt’s publisher, for whom he faithfully provided written accounts of his adventures.

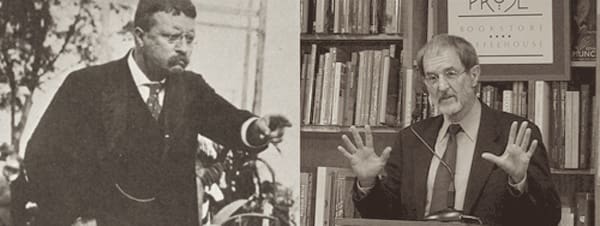

Therein lays the nexus between Colonel Roosevelt and his modern-day biographer. Edmund Morris was born in Nairobi, Kenya, where legend of Roosevelt’s Safari exploits deeply impressed him as a boy. Morris was further drawn to write of Roosevelt as he discovered that Roosevelt was a successful and established historian and author, a fact frequently obscured by “Teddy’s” larger than life mystique.

Otherwise, there seems to be little very little in common between the two men. Roosevelt’s robust life was filled with action and adventure, and he frequently smelled of sweat or taxidermy chemicals. On the other hand, Morris is a slight pale man who looks like he spends his days in the bowls of artificially lighted archives searching through obscure primary source materials. Roosevelt was most at home on a horse with his favorite lever-action Winchester in hand. Meanwhile, you can imagine Morris quivering with nerdish delight when he tells of discovering long-forgotten anecdotes over a glass of his favorite Chardonnay.

The contrast between the men is in full evidence in Morris’ writing. He portrays the Colonel as though observing an alien from another world – from a time and a place where metrosexuals were derided as dandies. Roosevelt’s masculine endeavors are described with an air of amused condescension. Throughout, Morris’ prose is filled with polysyllabic words, arcane usages, and foreign languages quips, so in addition a thesaurus, you’ll want to keep French, Spanish, German, Greek, and Latin to English dictionaries on hand while you read. Roosevelt spoke and read all of these languages fluently, but his own writing was surgically blunt.

Nowhere is the difference between the two men more stark than Morris’ homoerotic description of the fireplace in Roosevelt’s trophy room (p. 125):

Years of creosote deposits had darkened the cannonballs that lay like testicles at the base of two penile, brass-sleeved shell cartridges serving as andirons in the hearth.

Yet somehow the clash of personalities works. Extraordinarily well. The quirkiness of Morris’ writing style effectively transports the reader a hundred years back in time. Or as my son James, observed, “You almost forget that Edmond Morris is writing and that it isn’t just the transcript of Roosevelt’s life.”

Gun lovers might be a little miffed that Morris does not spend more time describing “the most magnificent rifle ever made,” the .500/450 Nitro Express Holland & Holland ‘Royal’ double-barrel that was gifted to Roosevelt by fifty-six English dignitaries for hunting elephant in Africa.

Nor does Morris make much mention of Roosevelt’s beloved Winchester Model 1895 in .405 Winchester that the Colonel called “Big Medicine” for hunting lion. The Model 1895 lever-action features a box magazine rather than tubular, and was capable of hurling the 300 grain .405 caliber bullets at 2230 feet per second. Roosevelt insisted on taking three of them to Africa.

Right in front of me, thirty yards off, there appeared from behind the bushes which had first screened him from my eyes, the tawny, galloping form of a big maneless lion. Crack! the Winchester spoke; and as the soft-nosed bullet ploughed forward through his flank the lion swerved so that I missed him with the second shot; but my third bullet went through the spine and forward into his chest. Down he came… his hind quarters dragging, his head up, his jaws open and lips drawn up in a prodigious snarl, as he endeavored to return to face us. His back was broken… His head sank, and he died. — Theodore Roosevelt

And there is no mention whatsoever of the custom 12-gauge, double-barrel shotgun given to Roosevelt for the 1909 safari expedition by the Ansley H. Fox Gun Company (auctioned on October 5, 2010 by Julia’s for $862,500, the highest price ever paid at auction for a shotgun).

Morris does, however, note that Roosevelt’s first kill in Africa was of a Thomson’s gazelle at 225 yards with a “Springfield .30.” In total, Roosevelt bags nearly 300 game animals including “9 lions, 8 elephants, 6 buffalo, 13 rhino, 7 giraffes, 7 hippos, 2 ostriches, 3 pythons, 1 crocodile, 5 wildebeest, 20 zebras, 177 antelope of various species, from eland to dik-dik, 6 monkeys, and 32 other animals and birds.” Morris cannot resist but to opine, “the paradox that hunters are practical conservationists, needing to preserve what they pursue.”

Morris does not invoke this same tone of superiority when writing about Roosevelt’s politics. Unlike other Roosevelt biographers, he remains decidedly neutral, allowing the reader to impose their own ideologically tinted conclusions.

As if stories of Colonel Roosevelt tracking outlaws in the Dakotas, leading the Rough Riders against the Spanish in Cuba, staring down Kaiser Wilhelm II over Venezuela, or his African safari exploits were not evidence enough to enshrine the former president into to the hall of American iconography, Morris recounts the attempted assassination attempt of Roosevelt at a campaign stop in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. At the time Roosevelt had bolted from the Republican Party and was the presidential candidate of the short-lived Progressive Party. John Flammang Schrank emerged from a crowd and shot Roosevelt in the chest at close range. Members of Roosevelt’s entourage quickly disarmed and restrained the man.

Meanwhile, Roosevelt had hoisted himself up in the tonneau [of a waiting car]. He was shaken, but did not appear to be bleeding. For the moment, nobody but he realized he had stopped a bullet. He looked down and saw that [Elbert Martin, Roosevelt’s stenographer] was trying to break Schrank’s neck.

“Don’t hurt him. Bring him here,” Roosevelt shouted. “I want to see him.”

Martin’s blind rage cleared, and while still half-throttling his prisoner, he dragged him to the side of the automobile. Roosevelt reached down and, in an oddly tender gesture, took Schrank’s head in both hands, turning it upward to see if he recognized him.

What he saw was the dull-eyed, unmistakable expressionlessness of insanity, along with clothes that looked as though they had been slept in for weeks, and an enormous pair of shoes…

“What did you do it for?” he asked, sounding more puzzled than angry. “Oh, what’s the use? Turn him over to the police.”

After Roosevelt saw that he was bleeding:

“He plinked me, Harry,” he said to [Harry F. Cochems, chairman of the Progressive Party speaker’s bureau].

Roosevelt refused his handlers’ pleas that he go immediately to a hospital. Instead, he proceeded to a scheduled speaking engagement.

Cochems preceded him to the podium… informing the audience — ten thousand strong, with at least as many milling outside — that Roosevelt had been the victim of an assassination attempt.

“It’s true,” [Roosevelt] said. “But it takes more than that to kill a bull moose.” There was some nervous laughter, so he unbuttoned his vest and exposed his shirtfront. The spreading bloodstain, larger than a man’s hand, caused screams of horror.

“I’m going to ask you to be very quiet. I’ll do the best I can.”

Roosevelt spoke for an hour and twenty minutes, then politely excused himself and finally consented to receiving medical care. But, before he allowed a surgeon to examine him on a hospital table, he had one last request.

He [asked] that somebody contact Seth Bullock [legendary frontier law man and friend of Roosevelt’s], of Deadwood South Dakota, and be sure to mention that he had been shot with “a thirty-eight on a forty-four frame.”

If you have read and enjoyed either of the first two volumes in Morris’ biographic trilogy, there is nothing in Colonel Roosevelt that will disappoint. If you have not read the previous two volumes, don’t feel you have to in order to enjoy Colonel Roosevelt, as the narrative is self-contained. As with its predecessors, Morris meticulously documents Colonel Roosevelt. The tome is 784 pages include about 150 pages of notes. If you, as I do, read the end notes, this is a very long, but satisfying, read. Colonel Roosevelt is a worthy conclusion to Morris’ epic history of “the most interesting American who ever lived.”

[Random House provided an advanced review copy of Colonel Roosevelt for this review.]

I used to admire Roosevelt. That is, I did, up until the time I started reading up on his politics. I learned that he and Woodrow Wilson were at the epicenter of the start of the Progressive movement that has proven to be such a cancer on our Nation. Sure, Roosevelt was a hero. He was an outdoorsman, conservationist, adventurer, hunter, and a dozen other positive things. But his political beliefs put this country on the road to ruin.

I’m reading an interesting book right now, too. 1920, the Year of Six Presidents covers the election (where Roosevelt would have almost certainly been the Republican nominee, had he not died) and the men who vied to succeed Wilson in the Oval Office. It’s a fascinating read, because unlike what we’ve been given to understand about politics, this was not a battle between “Conservatives” and “Progressives.” It’s been between “Progressive” and “Progressive Lite” (just like the last election between Obama and McCain). In 1920, not one candidate stood on defense of the Constitution and the principles of our founding fathers. Because of it, we find ourselves in a situation where the ObamaNation claims the government has a legal right to force citizens to buy something (health insurance) and looks at the Bill of Rights as more of a “List of Suggestions” than the law of the land.

And it all started with Roosevelt. Pity.

Brad, I can’t disagree with anything that you have said. Roosevelt certainly opened Pandora’s Box. But please consider the following before judging TR too harshly:

1. TR was exceptional when it came to executing the responsibilities of the presidency that are specifically mandated by the constitution: foreign policy, national security, CINC of the armed forces, and nomination of judges and other federal employees.

2. In Roosevelt’s era, there was legitimate need for reform. You had extremely hazardous work conditions for many blue collar workers. You had children working, sometimes in hazardous conditions, sometimes pimped out by their parents. You had an epidemic of drug-addicted housewives guzzling tonics (aka snake oil) unknowingly laced with opium and popular sodas full of cocaine. Etc. I think most modern “conservatives” would agree that they believe in limited regulation and small government, not ‘no government’ or anarchy.

3. TR did not have the benefit of 100 years of hindsight to show him the thousands of failed/corrupt Big Government programs and regulations. He was nothing if not an astute student of history.

4. TR’s views on conservation and civil rights were right on. These issues did not become perverted into wealth redistribution schemes until 40+ years later. I find it impossible to believe that TR would endorse what these movements have become today.

5. For all of TR’s bluster about trust busting, he actually did quite a bit less of it while president (7-1/2 years) than his “pro-business” successor, Taft, did in 4 years.

I have great, great admiration for TR, but I would only call him a self-made man after I made it clear that he was born into a very wealthy family. When he suffered breathing fits, his father would rush him into the family coach for invigorating rides at all hours. His father bought the entire family the best exercise equipment available. TR did remake himself from a sickly child into a paragon of health and vigor, and challenged himself throughout his life, but had he been born a Cratchett he may well have died as a child or lived a brief, sickly life.

Other than that quibble, I enjoyed the article.

I hesitated to use the “self-made” descriptor for the reasons you correctly state. Furthermore, you could argue that his father’s reputation opened some doors for him when he initially got into politics.

However, I went with it because he made his own money from writing at an early age – his first published book The Naval War of 1812, written while he was still in college. And his political career was undoubtedly made by his unrelenting force of will, boldness (attacking the “smoke filled rooms” and political bosses of the day), intellect, ability to master bare-knuckle political brawling, and hyper-competence in office.

Comments are closed.