The 1860 Henry wasn’t the first repeating rifle. That would be the 1848 Volition Repeating Rifle. Nor was it “the gun that won the West.” If any single repeater has a claim at that title, it’s the 1873 Winchester.

The Henry was neither, and yet at the same time, it was more important than either of those guns. The Henry was the rifle that proved the entire concept would work. Work on the farm, work on the battlefield, and work on the frontier.

The Cimarron Firearms Uberti 1860 Henry is an exceptional copy of the original Henry Repeater. It’s a faithful reproduction of one of the most important firearms in history. It’s also perfectly functional, still relevant, and just plain ol’ gorgeous.

Designed by Benjamin Tyler Henry while he was superintendent of the Winchester rifle plant, Henry took the failed Volcanic rifle and made significant improvements. This occurred right at the start of the Civil War, and I’m sure the fledging company recognized the gold mine in brass and steel they were had on their hands.

Proving that things never really change, the bean counters and perfumed princes of the United States Army missed the point entirely. They figured the soldiers would waste ammunition if they had the ability to shoot so much, and feared the rifles to be too delicate for use. Still, some 14,000 were made.

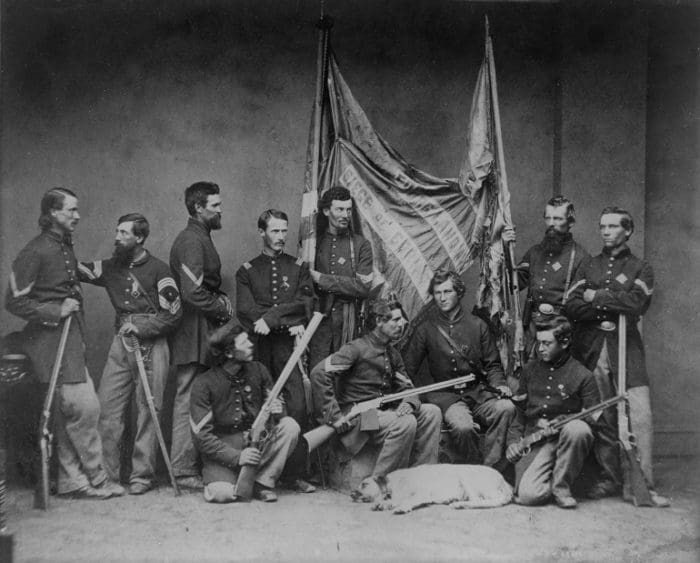

Most of those went out to about 40 U.S. Infantry and Calvary units, and most of those from Illinois. A few made it into the hands of Confederate troops, most notably the bodyguards of President Jefferson Davis as well as a few units of the Texas Calvary.

I have no doubt the Texas cavalrymen understood the value of the repeating firearm, having learned the hard way that mobility and audacity can make up for muzzle energy and precision in their fight against the Comanche. The rest of the military, on both sides of the conflict, appear to have either never learned or forgotten the concept that, in war, mobility equals life.

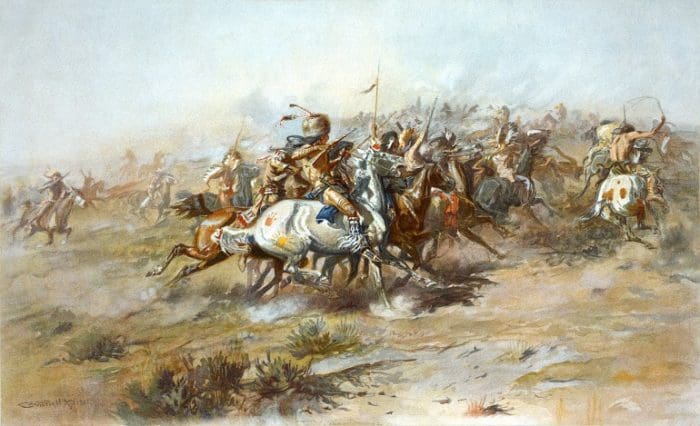

Unfortunately for General George Armstrong Custer and the more than 700 men under his command at the Battle of Little Bighorn, that was a lesson that the plains tribes of the Lakota Sioux, the Arapaho, and Cheyenne didn’t forget. While General Custer chose to leave his Gatling guns at camp and arm his men only with single shot Springfield trapdoor rifles, his opponents were on horseback armed with Henry and Winchester repeating rifles, and plenty of ammunition. They also vastly outnumbered Custer’s men, and were ready for a fight. The result was annihilation for the men of the 7th Cavalry.

For a good quick read on the original Henry repeater, I highly recommend Andrew Bresnan’s article “Victory Thru Rapid Fire, available online.

This Henry repeater is made for Cimarron by Uberti Firearms. Cimarron claims that these rifles are made to their specifications by the Italian firearm maker. I’ve always been impressed with the guns put out by Uberti, and the excellent quality and historical accuracy of the Henry repeater was no surprise.

True to the original, the lever is locked down with the turn of a small tab. For lever-action firearms with larger cartridges, or stiff actions, that wouldn’t be necessary. Considering the very short throw of the lever required to expel and chamber a round, as well as the fact that the rifle was designed to be used on horseback, this lever lock isn’t just a good idea, but a necessity.

The wood is a straight-grained walnut, and of a quality that I wish I found on most American made rifles. Yes, good wood is expensive, but it’s worth every penny. Some of the photos on the Uberti website show rifle stocks with much greater figuring in them, but I haven’t seen that grade of wood on the rifles on the shelves at Texas Jacks Wild West Outfitters, or on this rifle.

That wood stock ends in a curved brass butt plate. The wood-to-metal fit has been done well throughout the firearm, better than I see on most American-made guns. Note that the screws that hold the butt plate to the stock are color matched to the barrel, and are correctly timed. Nice touch.

There are several models of the 1860 Henry available on the Cimarron Firearms website, with several finish options available as well. This gun is the 1860 “Civilian” model with a 24-inch octagonal black blued barrel. I highly recommend everyone take a look at the early model steel framed version.

Unfortunately, none of the museums around me had an original 1860 Henry I could handle. But I do have a decent little library of old gun books and I had plenty of pictures to judge this version against. Most of those included the military model, which had sling attachments included, (also available from Cimarron) but even so, it was easy to get a good look at what the gun was supposed to look like.

Cimarron absolutely nailed it. Every color, every finish, every cut and mark appears correct. Cimarron’s literature says that this gun was copied directly from an original in Cimarron’s private collection. I imagine it was, or else they had detailed access to one.

Then again, I’m not surprised. I was able to compare their McCulloch Colt to an original at the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum and the level of detail they got right on that one was almost eerie. If this rifle wasn’t marked with the model, maker, and importer as required by law, most folks would have a very, very hard time telling it apart from one of the rare originals.

The devil is in the details, so to speak. For instance, note there are in fact several models, with fairly minor differences. According to everything I can find in my books or online, this is exactly the same as the originals. The minor differences in finish also matter. Take a look at the lever loop. The color case hardened metal has been done perfectly.

Most of the screws on the gun are black, like the barrel, and timed appropriately. Most, but not all. That one at the muzzle has also been finished differently, and beautifully. Although all of the photos I can I find of that detail in my books are black and white, they all show the obvious difference in finish as well. That’s attention to detail that most companies wouldn’t have bothered with, but it makes all the difference in the world.

If you’re just familiar with the loading gate, the 1860 Henry’s loading process will seem like absolute witchcraft. Just…even slower. First, clear the rifle and turn it over. Now push the follower all the way up until the bar indicator on the front of the muzzle pushes out about 1/16th of an inch. Then, and this feels like opening a some magic lock, rotate the entire mechanism around the gun to the left.

After that, simply pour rounds into the gun until you can’t anymore, rotate the block back around, cycle and shoot. It’s actually possible to load one at a time as an emergency or “administrative” reload. Unlike most other lever-action guns, although it is possible, it is not particularly simple. It’s a skill that can be mastered, but I certainly didn’t have time for it.

The literature says that it will hold 10 rounds. I had no issue at all getting 12 into the magazine. Assuming you’re extremely careful during the reloading process, it’s actually possible to keep one in the chamber and still load a full magazine without violating any of the four basic firearm safety rules, giving you a total of 13 rounds in the gun. That’s actually less than the original, which could hold as many as 16.

What made the Henry so amazing wasn’t just that it was a repeater, but the metallic cartridge that allowed it to be so. That original .44 caliber rimfire cartridge wasn’t widely accepted by the government partially because it was considered underpowered for military use.

Firing a 200 grain lead round at about 1,100fps, it was no slouch by modern pistol caliber carbine standards. After all, that gives it about as much muzzle energy as the .357 Magnum. But that 200 grain bullet must have seemed awful puny next to the 500 grains of lead pushed out by the Springfield muskets of the time, which put out about double the amount of energy at the muzzle of the Henry.

This modern rifle is available in two cartridges, the .45 Long Colt and the .44-40 Winchester. Also known as the .44WCF, the .44-40 is a round that is commercially available with loads that mimic the original .44 Henry Rimfire perfectly.

This particular lever gun shipped in .45LC, an old, but not quite that old cartridge. It wasn’t invented until 1872. What it lacks in authenticity it certainly makes up for in commercial availability, as well as extreme versatility.

For the reloader, the .45LC is probably the most under-utilized and under-rated cartridge in common use. Duplicating the original .44 Henry Rimfire ballistics was easy, and well under the performance capabilities of the cartridge.

For this review I did exactly that, shooting 100 commercial Winchester Cowboy Action Lead Flat Nosed rounds, and then shooting another 150 of my own reloads. Given the barrel length, 9.6 grains of Unique and a well lubed 200gr flat nosed round should have gotten me pretty close to the original ballistics of the round fired into General Custer’s ill-led men.

Neither the commercial load or the closer-to-the-real-thing facsimile load produced anything I would even call recoil. If you’ve shot a single shot single shot .22LR, you’ve felt a similar feeling on your shoulder as this rifle when it’s fired. Of course, at a little over 9lbs, you wouldn’t expect it to.

Combine the light recoil, the short length of the cartridge, added to the simplicity of the mechanism, and you end up with an extremely fast action. In slow fire, you can definitely feel mechanism working, the rise and fall of the block to reload the cartridge. But it’s all very smooth, with no catches or spots to slow you down anywhere in the cycle.

I’m not much of a cowboy action shooter, and still I could easily keep 4 shells in the air while shooting. Spend a little time on YouTube, and you’ll see the better cowboy action shooters with 7 empty shells in the air before the first one touches the ground, and every round hitting the target. After those 7, there’s at least another 6 behind them before you need to reload. Somewhere, a California legislator’s head is exploding.

At no point in the 250 rounds I fired for the review did the Henry 1860 by Cimarron have any issues in function. It never failed to load properly, feed properly, eject or fire. As long as my hand moved up and down on that lever and nothing got in the way of the follower, the gun did its job perfectly.

That said, one of the original complaints of the rifle’s design was on full display during testing. As you can see, there is no fore stock. If you are firing off a rest, the magazine tube sits directly on the rest. That means the spring as well as the follower tab also sits on the surface of whatever you have the gun sitting on and it will certainly get caught or stuck on that surface as it moves, causing a failure to feed.

Of course, that also includes your hand. I had to keep special attention to my hand position under the rifle. If the magazine was fully loaded, I had to move my hand out-of-the-way of the follower as it came back toward the receiver while feeding. If only 5 or 6 rounds are loaded, I rested my hand beyond the follower position anyway, and it wasn’t an issue. This certainly takes some getting used to, and I never quite got the hang of it during the review.

The front sight is period correct, and is a simple, un-shrouded metal blade. I have read in some places that the originals were German silver, but that is hard to believe as it is both expensive and soft. This front sight stood out well in bright light as well as on a stormy day, but it was a bit too wide for very precise work. Still, accuracy was far better than good enough.

Using the commercial Winchester rounds, I was able to score an average 3 1/4″ five shot group for four rounds off a Caldwell Stinger Shooting rest at 100 yards. My own hand loads scored only slightly better, averaging right at 3″.

The rear sight is also correct, with a notch and a flip-up elevator sight. Considering this was essentially a 3 MOA gun with my eyes and the iron sights, and the ballistics closely matched the original rifle, I wanted to see if the range marks on the sight were correct. I find it doubtful that the 700 and 800 yard mark are particularly useful on this particular gun as at those ranges the round has less energy than a .22LR does from a pistol’s muzzle, but the 300 yard mark is still of some value, delivering the energy a 9×19 would at about 30 yards.

So using the same rest and my homemade round, I put the elevator up to the 300 yard mark and sent five rounds down range at my 300 yard steel. Sure enough, I was rewarded with 5 (fairly faint) rings, and a roughly 10″ group slightly high to the right on the target. Ha, it works!

That’s just one of a hundred details on this gun that Cimarron got just right, I hope that fewer words and more photos will be able to show the reader some of them. It’s a beautiful gun.

For me, this gun was a joy to shoot. The historical importance, as well historical accuracy of the rifle made this review interesting. Just as interesting is that, by any reasonable standard, this is a “weapon of war.” It’s capable of a high rate of fire, killing accurately at a distance, and the original holds almost as many rounds as the M16A1.

It was an actual military weapon, exactly as is, and it was effectively used by insurgents against the United States government to kill US personnel. And any child can operate it effectively! I think it’s safe to say that this gun, almost 160 years old, is just barely legal in some states. And come one, that’s just plain fun.

This is the gun that started it all, that proved the concept, and will remain an indelible part of the American story. Cimarron has done it justice.

Specifications: 1860 Henry Civilian in .45LC

SKU: CA288

Caliber: .45 LC

Style: Henry Civilian

Capacity: 12 (ish)

Frame: Brass

Finish: Standard Blue

Barrel: Length: 24.5″ Octagonal

Barrel: Twist: 1:16RH

Stock/Forearm: Walnut

Overall Length: 43.3″

Weight: 9.05 Lbs.

MSRP: $1,459.00

Ratings (out of five stars):

Style and Appearance * * * * *

This rifle gleams and glows. The details are all there and they’re done right.

Historical Accuracy * * * * *

I was going to take off a star because it’s the wrong caliber, but it’s not possible to chamber it in the right one. Kudos for everything being right, down to the smallest detail.

Reliability * * * * *

It works perfectly. Keep in mind where the magazine follower is.

Accuracy * * * *

As it is, it would have taken sub-three-inch groups to get a full five stars here. Still, the rifle displays a precision well beyond the reasonable ballistic limit of the round it fires.

Overall * * * * *

I judge these replicas not just on historical accuracy, but how I would have judged them at the time they were released. Like soldiers on both sides of the Civil War did, I would have given well over a month’s pay to be able go to war with one of these rifles back then. It represented a giant leap forward in combat effectiveness, and ushered a new way of mobile, fast fighting across the continent.

Cimarron’s 1860 Henry Repeater by Uberti is an example of exceptional attention to detail and quality at every turn. This is a fantastic gun.

“That damned Yankee rifle you load on Sunday and shoot all week long”

🤠

From where I sit, the magazine follower design was a critical flaw in the Henry. The “Henry Hop” makes my blood boil on the sheer stupidity of it. For cowboy guns I’m a big fan of the Schofield and the Winchester 1873. Both are decades ahead of their time. (While the Schofield was underpowered by the standards of the day, it’s ease of reload makes up for a multitude of sins.)

Remember the times, serge. Most folks were using single shot muzzle loaders at the time. And I’m sure that with war clouds gathering there was a hurry to get the job done.

The company that really screwed the pooch during that war was Smith & Wesson. They had patents that made them the only company that could produce bored through cylinders for revolvers. What did they do with this technology edge? They made .22 and .32 rimfire revolvers. These revolvers sold well but S&W lost a chance to run Colt and Remington out of business by not making a big bore service revolver.

“Designed by Benjamin Tyler Henry while he was superintendent of the Winchester rifle plant…”

No. There was no Winchester plant at the time. The plant was known as the New Haven Arms Company. The company was not named Winchester until Nelson King improved the Henry design and came out with the Winchester Model 1866. The 1866 design evolved into the Models 1873 & 1876. The Model 1886, designed by John Browning was a whole new design.

The Henry design was genius in that the actual Henry rifle was only manufactured for 6 years but its direct offspring, the Model 1873, was manufactured until 1923. Of course replicas are now being made by many companies.

Yes. Winchester plant. That exact same ground would be owned by four different companies. And yet, for over a century, it was best known as the Winchester plant.

Yeah, right, whatever.

Actually, the real story of manufactor of these rifles is more interesting then the rifle. Henry entered into an agreement with Oliver to make the rifles for Winchester. Oliver paid a flat rate for the guns. Henry made a bit of money, more then he would have as an employee of Winchester, but lost his patent in the process. He eventually went his own way and Oliver took Winchester to the top. This is a very short and not necessarily accurate account, that would take pages and has been written. Look it up.

This is the “About Guns” I really enjoy. Thanks for the links, as well.

“If the magazine was fully loaded, I had to move my hand out-of-the-way of the follower as it came back toward the receiver while feeding.”

That motion is called: “The Henry Hop”, because with practice the follower can hop over the support hand in recoil.

That’s a beautiful rifle.

I’m wondering though. Could you get a decent cheek weld and still use the sights?

That’s a huge drop on the comb of the stock.

Standing I could get a pretty good weld, but not seated or from the prone.

The federal .gov committed to the Spencer repeater. It was cheaper and had a marginally superior round. They bought 90-100 thousand spencers during the war.

Before the war had ended they started R&D into a single shot cartridge breechloader which would eventually become the Springfield rifle and carbine.

Almost as soon as the war ended the Army got rid of the Spencers. Selling them on the open market or letting demobbed soldiers take them, for a cheap price, home.

There was no one gun that won the west. That was pure Hollywood hoakum.

If only it was available in .44 mag

amen.

seems to me a nice wooden shroud surrounding the magazine tube that was slotted for the follower would allow for hand purchase and negate the need to reposition your hoppity hooper.

Sharps and Remington rollers made the West safe for the Winchesters….

And Colt made it safe for them.

“Somewhere, a California legislator’s head is exploding.” We can only hope.

Great review of a great gun. I’d buy one in a nanosecond if I had the $$.

How does it stack up against the Henry-brand Henry?

“General George Armstrong Custer” he was only a Colonel at Little Bighorn. Too many generals after the Civil War.

Custer’s general officer commission was “brevet”, meaning temporary, limited to the duration of the war. National Park Service reports Custer was a Lieutenant Colonel, acting as commander of the 7th Cavalry vice the actual Colonel ( Samuel Sturgis (1869-1886)).

https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/lt-col-george-armstrong-custer.htm

I have the .44-.40 version of this rifle, and all I can say is that it is a wonderful representation of the original. It is a beautiful piece of eye candy, and if you have a love for the cowboy firearms, then this is a must. I take mine deer hunting and must say it has never let me down.

I’m 6-5 and long arms

Can you get this in a longer barrel and longer stock

If you love to wear vests? so get this amazing Red Puffer Vest which is a favorite of all girls and it is the most-rated and most selling outfit in our store, shop now because the stock is limited.

Comments are closed.