By Trevor Zantos

On July 11th, 2006 I was involved in a fairly catastrophic motorcycle accident. My life changed in that instant and everything from that day forward, would be affected. I’m always happy to discuss my various experiences with anyone who asks, but I dislike volunteering information about my accident and the challenges I face because I’m not looking for pity.

Friends have suggested that it would be a good topic to write about and might help encourage someone else. What finally pushed me over the edge to do this was a post by someone on Instagram sharing a story about a cop who lost part of his trigger finger and was very discouraged, but had friends to support and push him to persevere and figure out how to get back to enjoying the hobby of shooting.

I thought it was an encouraging story and that was what got me to write this story in the hope that it encourages someone else to reclaim part of what they may have lost.

First, some background. I was 22 years old and I living the great life of a young, carefree bachelor. I had a job I loved as an apprentice machinist in the gun industry and would ride my motorcycle to work every day.

On that fateful day in July, I was headed to a friend’s house after work to play poker when an SUV suddenly stopped in the middle of a single lane turn with nothing in front of them. I was already leaning over for the turn going 30mph (motorcycles don’t like stopping in turns) so I had to decide — quickly — whether I wanted to lay it down and maybe run into the back of the SUV or try to go around on the shoulder.

I chose the shoulder, not realizing that construction around the site had left a bunch of debris there. The debris grabbed my tires and pitched me off the bike into a concrete barrier. I bounced off the barrier into the handle bar of my motorcycle and then slid on the asphalt on my face for about 50 feet where I finally came to a halt.

As I tried to understand what happened, I flipped myself over and realized I couldn’t use my right arm. I used my left arm to undo my helmet and saw blood pouring out of my right arm. I couldn’t feel my legs and I knew I was pretty badly hurt.

I had a bit of medical training from some of the shooting classes I had taken and knew that staying calm was the key to not accelerating my blood loss. Fortunately, a Good Samaritan stopped behind me and called 911 and my parents.

Emergency services arrived, but the one thing I cared about was making sure the California Highway Patrol officer knew I was a licensed concealed carry holder and I was carrying a gun. This happened in Southern California so concealed handgun carriers were relatively rare and I didn’t want my gun going to an evidence lock-up (it was a Ted Yost 1911…priorities!).

The officer went above and beyond and stayed past his shift to locate my paperwork and gave the gun to my parents. I don’t know his name, but I certainly appreciate the kindness he showed.

Over the next 24 hours I flat-lined — yes, I actually died — a few times. My parents were told I was not going to make it, yet some very talented medical staff with a healthy dose of divine intervention managed to keep me alive.

There is a lot of medical nonsense involved, but for the purposes of this discussion I will be brief: I fractured my back and nerve damage from that affected several other areas. All three major nerves in my right arm were sliced through along with a compound fracture. I sustained brain damage (some would argue that was a preexisting condition), and compressed my neck severely, damaging the nerves in my left arm as well.

To say I had a few problems going on is an understatement. I remember a specific moment, shortly after being brought out of the medically-induced coma, where I couldn’t talk due to a breathing tube that had been shoved down my throat for eight days.

This was a precarious situation, as I was dealing with hallucinations from the drugs and head trauma, all while being unable to speak. I had to be alone with my own thoughts while trying to decide what to do.

I knew that I had to make a choice; I could give up and allow my body to die and see what the afterlife was like or fix in my mind the determination to live. I was scared. I was scared of not being able to walk, how bad all my various injuries would be, what my quality of life would be like. I was also scared of the fight to recover that lay ahead and would most likely last the rest of my life.

I knew I had to make this decision without knowing the full extent of my injuries (as it turns out, the doctors didn’t know yet, either) and what my future might look like.

I was raised by fantastic parents that got me interested in reading at a very early age. That interest combined with being homeschooled helped turn me into voracious reader. I learned a lot from these books about life, what it’s supposed to mean to be a good man, the importance of faith and family, the proper role of government…I could go on and on.

Essentially, these authors mentored me and shaped my mind and I believe prepared me for that moment. The books were as varied as Swiss Family Robinson as a boy, the Lord of The Rings trilogy, Tom Clancy’s books, John Locke, Ivanhoe, The Art of War, The Book of Five Rings, The Iliad and The Odyssey etc.

One interesting theme through time and cultures of all the books I mentioned is that the main characters struggled. All the civilizations understood that while the struggle may look different, struggle was an essential part of life and one needed to be prepared both physically and mentally for those travails, especially for developing mental fortitude.

As I lay there, stuck with all of those ideas bouncing around in my head, I was reminded of a phrase I had read by an old blind Presbyterian pastor, George Matheson from his 19th century writings. He talked about a “shadowed desert period” such as Moses went through after fleeing Pharaoh’s court or Jesus went through during his time in the desert. He described it as if not only was the hand of God not with you, but that it felt as if it had been specifically removed…and you were walking in darkness in a harsh land.

What resonated with me was that in that darkness I was now being tested, like Dantès in the Count of Monte Christo as he is thrown into Château D’If. I was in my own sort of prison, although, admittedly the ICU ward was better appointed than the Chateau D’If.

Eventually, I realized that I had to fight. My character, though young and still not completely formed, would allow me to do nothing else. For reasons still unknown, I was given the gift of life again and now it was my turn to shoulder the burden. I struggled to recover and still struggle physically. But the biggest challenge was not losing perspective, not allowing myself to wallow in self pity or obsess as to my situation.

A few months later I was finally moved out of the ICU and friends could visit. While I still couldn’t walk and my right hand/arm was useless, I had managed to get my mind to start rebuilding the pathways and I could move my left hand a bit.

One of my friends from work came to visit and brought a blue gun with a weapon light on it so I could use it for physical therapy to exercise my hand. The nurses freaked out a bit at first, but after the story was explained, they relaxed.

That’s what started me down the path of using shooting as rehabilitation. Over the course of the next several months I relearned how to walk, how to brush my teeth (left handed!), feed myself etc. and was finally released from the hospital. Even though I was/am still rather physically broken I knew I wanted to go shooting. I was determined to figure out just how bad a shooter I had become and start to figure out how I could get better.

It’s hard to describe the broad effect shooting and the surrounding culture has had on my life. Somehow, even though I didn’t grow up around guns, I was fascinated by them and was fortunate enough to start working in the gun industry at age 19 and that started me down the path of shooting being both my work and my hobby and how I ended up meeting great people that became dear friends.

I was never a high speed low drag operator, but I had started to take a decent number of classes and trained regularly (when ammo was a lot cheaper). I became a died-in-the-wool 1911 devotee — hey i was young — and managed to meet some of the great 1911 smiths of the time. I was fortunate to acquire a custom government Colt 1911 built by Ted Yost’s shop and even got to hang out there while it was being worked on.

Shooting for the first time after the accident was a nerve-racking experience. I was full of doubt and on the other hand excited for the opportunity to do something I had done before.

I had only left the hospital a month before. My right arm and hand were useless due to the nerve damage. My left hand had nerve damage and I had pretty significant muscle atrophy. I honestly don’t remember how well I shot. My friend who was with me swears it was a good group (he wouldn’t lie right?). He was impressed and I remember being happy with my accuracy.

On the other hand, after just a few mags I experienced immense nerve pain and struggled operating the gun smoothly and knew the path ahead was going to be a long one. I had the overarching goal of becoming a better shooter than I was before my accident but that was something far in the future. I had to first relearn how to shoot, this time one-handed with what used to be my off hand.

I realized that while there were a lot of things I needed to practice, I planned on leveraging every industry contact, every gunsmith, shooting friend and my own research to try and find the best gun/configuration for my injuries at that specific time.

I encourage you, if you have injuries or disabilities don’t be afraid to try off-the-wall things, or niche activities. Some will work, some will not.

Another theme that I draw from the literature I read is embracing failure. If you don’t fail, then you are not risking enough because failure is how we learn and get better. I discovered that my 5-inch government 1911 wasn’t going to be the best gun for my injuries at the time, so I went off the board and tried a HK P7M8 squeeze cocker. It’s not a common gun, but its unique manual of arms and mechanics made it work better for me having to shoot one-handed at that time.

Over the years, I’ve tried a lot of different handguns, shotguns, and rifles. Some were right for the time and others just didn’t fit. It hasn’t been easy…honestly nothing about this is easy. I had immense pain at times and frustration at not being close to as good as I had been. I had all the other natural reactions resulting from a severe injury, trying to rehab, and dealing with disabilities that no one knew whether or not would improve.

For a while, my reality was that I could only shoot with my left hand. Eventually, over the course of a few years, I began to use my right hand as a support, which allowed me to improve my pistol shooting.

My next goal was shooting right-handed and then shoot carbines again. I had an ultimate goal of shooting 3-gun matches again and it took some years to get to that first match. With the great support of my friends I was able to finally do it.

I was horrible, and had to shoot part of the match left-handed because the nerve damage in my right hand. It just couldn’t take all the abuse.

Now, almost 15 years later, I’m still working to get back to the skill level I had before. I’ve run a bunch of different gear and guns, always trying to figure out how can I make these mechanical objects adapt better to my particular biomechanical difficulties.

My advice to anyone dealing with disabilities or injuries is to not be afraid of modifying guns so you can get out and enjoy your hobby again. The first step is always the hardest and there will be failures. But there will also be triumphs. I have my good days and my bad ones, but overall my journey through relearning how to shoot has been an important part of my physical and mental healing.

I leave you with this encouraging speech given by President Theodore Rosevelt from 1910 that has helped me when I wanted to withdraw from life.

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

I’d like to thank the author for the attitude adjustment he just gave me.

2 years back while on my bike, I got my ankle properly crushed. The author’s road back was far longer and far harder than mine has been, and I have far less to whine about.

So a sincere thanks for putting me in my place, so to speak. 🙂

I am back on the bike, but take far less chances than I had in the past…

“ I’d like to thank the author for the attitude adjustment he just gave me.”

Ditto.

Wow, what an inspirational story. I especially love the TR quote.

Thank you for sharing.

A preacher once said, “There aren’t roses all the way but all along the way”

Bravo Zulu, sir.

Well said.

Well done.

Very well written. Thank you for sharing your experience and what you have done to overcome. Impressive.

I wish you well on your way to recovery.

Excellent testimony; just excellent.

You Sir have Made my day. Tomorrow I go under the knife to have some issues remedied which will lay me up for some time. Nothing on par with your hurdles, but the inspiration you have shown in your journey gives me cause to know in all things there mountains to climb and hardships to endure. Thank You for the inspiration to push through and fight on.

In Liberty:

Darkman

Good Luck, DM, will be thinking of you.

I agree with Steve. Good luck tomorrow Darkman. I hope all goes well and you are back at it soon.

Praying for you. And good luck.

Thanks guys…Just got out of surgery a little while ago. Things went better than expected. Still a long road to go, but things will get better with time. Be Safe Out there and as Always Keep Your Powder dry.

Glad it went well.

Do what they tell ya. Healing will be faster that way.

“This was a precarious situation, as I was dealing with hallucinations”

I spent 21 days in the hospital and know exactly what you are talking about. Hospital psychoses is real, especially when the extreme pain meds are being pushed every two hours. One night I lost it. Didn’t know who I was, where I was, blind panic, seeing people in stupid mirror by sink. It was bad. Luckily my nurse that night had done time doing mental health community outreach. She said “I got you” and that’s why I think Nurses are Heroes. Her voice was my anchor. Your picture is hard to look at, very.

Good job pushing through your injury’s. I know you had some ‘dark days’ (what I call them) Try not to remember those.

We often forget how strong and capable we are until something comes up which tests us. We are all a lot tougher and more competent than we might think.

Well said.

Wow. That’s all I can say.

will o’ the wisp.

can o’ corn.

September 19, 2020, I suffered a massive heart attack and except for the grace of God should have died. I was not afraid to meet my Maker, but at the same time was determined that if I was able, I would live to see my granddaughter who was due to be born in November. Life is too precious to give up on!

Mine was November 8 2012. I went to a hospital where I had worked. Being on both sides of the situation really changed my perspective.

I have three friends I served with lose their mobility in one way or another. I lost one friend in iraq. One in afghanistan.

I lost touch with everyone, but still consider them friends and always will. I remember the road to recover that those friends shared, and how the loss of others affected us all greatly long after it happened. Not a day goes by I don’t relive the scenarios. Not one day.

When I got out, I struggled, eventually giving into substances and wallowing in my own self pity. The road to recovery was hard, and littered with relapses. I know now, I’m still not out of the woods.

I was never injured, or suffered a physical impairment, but mentally I have been scarred. I don’t know a single soldier that wasn’t. Guns, shooting, the community, the commitment, the understanding of as well as reasons to – and mentality behind carrying daily, and finally organizing locally have all been a HUGE help. I shut everyone out, and guns helped me find friends again. Patriots. Like minded free thinkers. And overall just people who enjoy the sport of shooting.

I highly encourage catching the bug, and learning how to mentally respect yourself and the gun, as well as the responsibility you have by simply owning even just one. It’s more than a self defense tool, much more.

Had to stop reading to comment. As someone who has inserted a lot of ET tubes over the last quarter century I’d like everyone to know that we don’t “shove” the ET tubes in.

Glad you survived. I’ve been on the ER end of many stories like this and a lot of them do not have happy endings. We use the term “donor cycles” for a reason. Now I’ll scroll back up and read the rest.

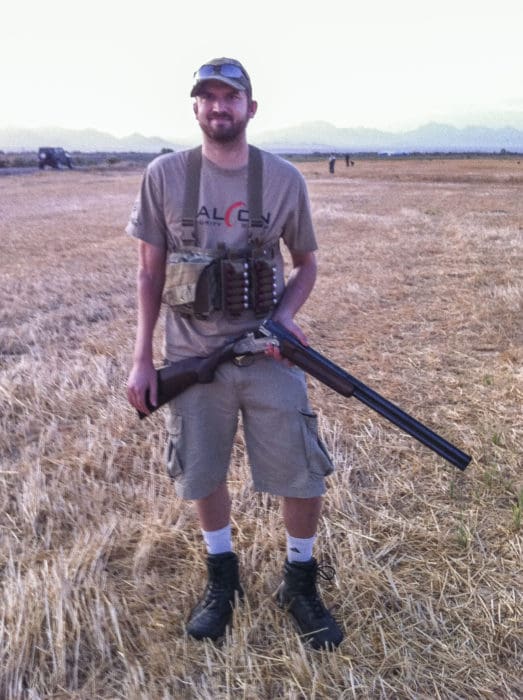

I note in several of the pics you are shooting right handed. That is awesome. I’m glad you survived and glad you have made a lot of progress in your recovery. Your story is very inspirational and will undoubtedly help a lot of people. It has already helped several here.

Always remember that fail is a verb, not a noun. It is something we do, not something we are.

Comments are closed.