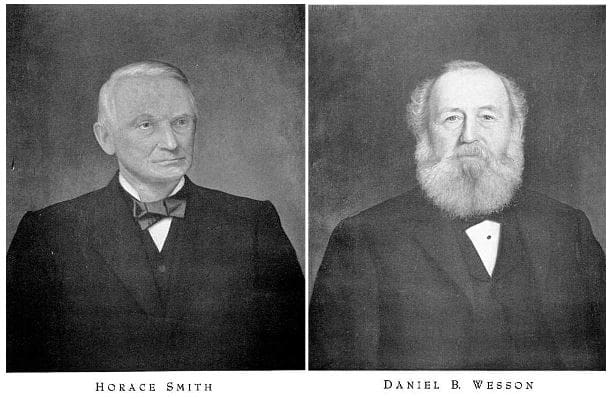

Horace Smith and Daniel Baird Wesson officially began Smith & Wesson on November 18, 1856. Company records in possession of Smith & Wesson historian Roy Jinks reveal what it cost to get the company up and running.

Mr. Smith contributed $1,663 and Mr. Wesson contributed $2,003.68. Why the amounts are odd numbers is anyone’s guess. Perhaps it’s all they had at the time.

Former Colt employee Rollin White held the patent on the idea of a bored-through cylinder, so they also had to pay for the use of his design. That cost them a flat fee of $497, with an additional royalty of 25 cents per gun.

That initial startup cost paid off handsomely. By October 1865 – just shy of nine years later – the local paper in Springfield, Massachusetts reported that both Horace and DB cleared $163,000 in annual personal income. They were the only two residents in the city with six-figure incomes.

Though much of the initial momentum can be attributed in large part to the increased production of arms and ammunition necessary for the Civil War, the company’s profits showed no signs of slowing in the following decades.

In 1873, at the age of 65, Horace Smith decided to retire. DB Wesson bought him out for $200,000 – or the equivalent of $4.2 million today.

In 1898, DB Wesson moved into a newly built mansion at 50 Maple Street in Springfield. Constructed of pink granite with a slate roof and bronze accents, the 3.5-story house cost somewhere between $350,000 and $450,000 to build. Adjusted for inflation, it would cost between $10.6 and $13.6 million to build the same house today.

All told, it cost $4,163.68 ($123,512.38 in inflation-adjusted dollars) to start a company that would go on to become a household name in the firearms business.

Logan Metesh is a firearms historian and consultant who runs High Caliber History LLC. Click here for a free 3-page download with tips about caring for your antique and collectible firearms.

glock 19

Shield.

Nice try though.

“Glock 19”

This !

Kimber!!!!! Springfield Armory!!!!!

Dan Wesson.

That’s what makes America great. Have a great idea, hard work, some investment and shazam…Capitalism at its best. MAGA

You forgot “get real lucky”.

Don’t forget “use someone else’s idea, just market it better.”

Such is the capitalist way. And will continue to be the capitalist way until the working proletariat wake up and violently rise against their bourgeoisie masters, redistributing land, wealth, and the means of production.

And then they fuck it all up for all and kill a lot of innocents. As they always did.

It’s too bad that later owners sold out to the Clintonistas. (See: Hillary hole.)

uhh yeah i am not gonna google that thanks.

Ahahaha!!!! That gave me a good laugh. Thanks.

Also, true. Very true. BAD Google, bad.

A black hole I don’t even want to contemplate.

They had the patents. They ruled the cartridge firing markets in the US. Colt and Remington were still muzzle loaders.

What did S&W do? Make rimfire pocket guns in .22 and .32 while the biggest war in American history was on. Had they enlarged their tip up guns and made them in .44 Henry rimfire they would have ruled the handgun market in the US for generations.

In another time and place they would have sided with Beta over VHS.

The army didn’t really want cartridges during the civil war though, especially not on infantry. Too new-fangled, untested and may explode on their own, plus they were expensive.

As for the idea they’d rule the handgun market if they made full sized handguns, that’s doubtful. Surplus percussion revolvers (including the 1858 Remington, which was well suited for cartridge conversion.) were dirt cheap after the war to the point Remington made mostly pocket guns post-war. It’s doubtful S&W would have had better luck with full sized. Until the Schofield (you know, the SMITH AND WESSON Model 3, which was made in .44-40) and Webly, with their ability to extract every case at once, the advantage of a new production cartridge gun over a converted cap and ball was minimal.

I agree with much of what you said, with the exception that the Model P was rapidly adopted over even converted cap and ball guns. Considering that it was so similar in dimensions, weight, and balance of the converted Colt Army’s, there must have been a good reason to for so many to shell out the extra money for the new guns, even though they extracted basically the same.

SAA was 1873, almost 10 years after the war ended in 1865. Most likely they surpluses their mismash of revolvers by then and had nothing to convert. Plus the 1858 was still the minority of US revolvers: Most were brass framed Colts. Those have a fairly short lifespan due to the weakness of brass and the poor stress distribution (1858s and that one Confederate revolver with their frame under AND above the cylinder are far more durable) to the point that even modern production ones don’t last that long. which is pretty good reason to drop them in favor of a steel frame with good stress distribution.

Spiller & Burr being the Confederate revolver.

Umm . . . Now, that there is a really bad mishmash of errors and misstatements.

Colt did NOT build brass-framed martial revolvers–not from the 1836 Paterson through the Dragoons, the 1851s, the 1860s, and right up to the last open-top cartridge 1872. ALL Colt revolvers of the era were steel-framed. Only the occasional Confederate maker used brass frames, because they could be cast; Colt frames were machined, and of steel. They DID build guns with brass trigger guards and backstraps, though–not the same as a ‘frame.’

The ‘1858’ Remington was NOT the primary martial firearm at the end of the Civil War, nor even during it. The largest-volume Remington was the 1863, and that partly due to the fact that the Colt factory, maker of the popular 1851, 1860, and 1861 models, burned down in 1864.

Colt, once back in business, made new parts on the open-top pattern right up to the retooling for the 1873 Model P; New parts were also made for the conversion Thuer and Richards models, and parts such as cylinders and entire barrel assemblies were made for the later Richards-Mason models. Colt made open-top cartridge guns after the expiration of the Rollin White patent that were not ‘conversions,’ but entirely new guns–although ‘conversions’ of customer guns continued into 1878.

Other than THAT, you’re spot on. Bear in mind that you’re dealing with people who KNOW these things; Try a little research first, before you post.

It was all revolutionary at the time. Once mainstream, only the best succeed.

Fun and interesting Logan. I always look forward to your work. More of it, and longer.

The writing I mean, the writing.

“The writing I mean, the writing.”

Suuuuuure… 😉

A very nice and informative article. ….Behold the S&W Plastic Gun.

They used to make guns in MA, CT and NY? So WTF happened?

I am curious to know how Smith and Wesson came up with the initial investment in the first place. Coming up with today’s equivalent of about $60,000 extra cash was EXTREMELY difficult in the years preceeding 1856.

This account also tells me that I should probably abandon any business endeavor that is not growing by leaps and bounds in the first three years. The major problem I have: it seems like it would take at least two years to completely plan and launch a major business: that is an awfully long time to be fiddling around and not actually producing your product/service en-masse.

And then it seems like you would eat up all of your early profits constantly expanding capacity to keep growing by leaps and bounds.

Finally the most important question of all: would you ever actually get to the point that you were actually stashing profits before the market evaporated? If you keep reinvesting forever, the market could collapse before you ever actually made any significant profit.

The Harley Davidson model would be to not expand production capacity to meet demand. Rather, raise your prices and make people order the product and wait for months. You’ll benefit from the increased margins without investing another dime.

Pull profits out ASAP. Produce with increasingly constrained supply until the market can no longer bear your prices. Then invest enough as necessary to maintain your prices – without growing so fast that there is no profit.

The profit is tied up in the value of the company- which is why the stock market is a thing. Owners can make money while growing as fast as needed.

Also: don’t invest with your own money- this is why banks are a thing- to cover investment without the cash outlay.

Recently I also opened my own business and really hope that it will flourish and I am doing my best for this. I found a very cool company whose financial consultants gave me a lot of useful advice. If you follow this link https://www.templarket.com/products/monthly-income-statement, you will discover a lot of new things. The monthly income statement example was very useful to me, which turned out to be the most relevant for me. It shows how revenue is converted to net income. The purpose of this monthly income statement is to show managers and investors if a company gained money or lost it during the reporting period.

I can imagine how difficult it is to make your idea pay off. But this does not mean that current startups have no chances. The main thing is to create a business, taking into account modern demand. Selling health supplements will be more useful than ever, besides, such a business is much easier to expand with the help of private label gummy manufacturer

Comments are closed.