By LKB

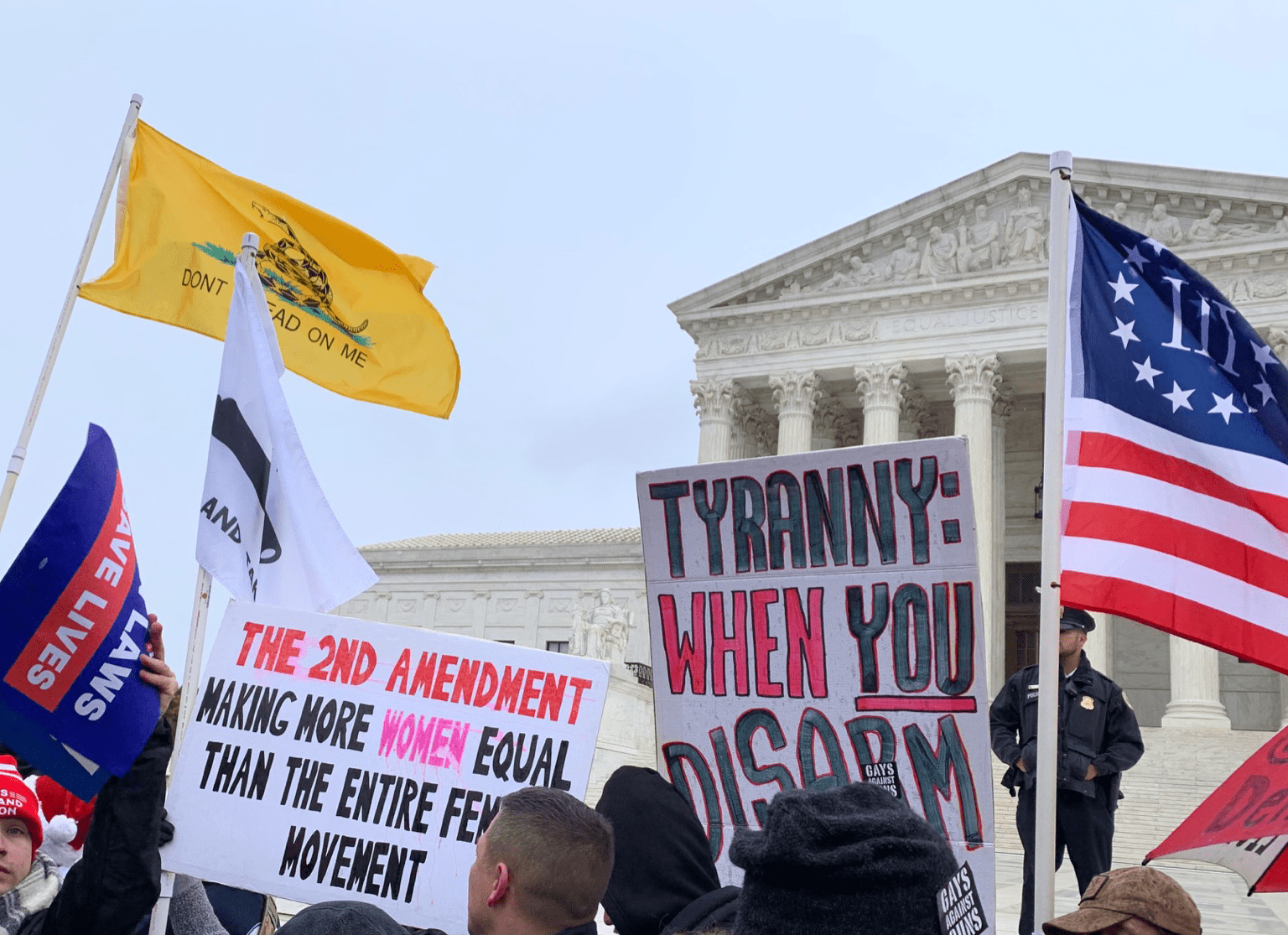

Like many of you, I am still processing the depth of the legal earthquakes from the Supreme Court late last month. With the 6 to 3 opinion in Bruen now the law of the land, the Second Amendment is no longer a “second class right,” and the test set out in Justice Thomas’ opinion likely dooms many other legal restrictions on firearms ownership.

While it will undoubtedly require more litigation (especially against recalcitrant states like New York and California), groups like the Firearms Policy Coalition, Gun Owners of America, Second Amendment Foundation, the National Rifle Association and many other Second Amendment think tanks now have the wind at their back, and I suspect we will see many such laws start falling shortly.

But as we look forward to the likely success of challenges to bans on modern sporting rifles, magazine capacity limits, efforts to perpetuate “may issue” regimes or otherwise prohibit public carrying, and potentially even the Hughes Amendment and some aspects of the Gun Control Act of 1968, it is important recognize the essential contribution of two particular scholars in getting us here: Don Kates and Sanford Levinson.

While they were not the first to argue that the Second Amendment needed to be taken seriously, in my opinion they legitimized scholarly debate on this subject. Their work sparked a renaissance in Second Amendment legal scholarship in the 1990’s that ultimately led us to Heller, McDonald, and now Bruen.

When I began studying constitutional law in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, the universal view of “mainstream” constitutional scholars was that the Second Amendment was little more than anachronistic window dressing, and provided no check whatsoever on governmental restrictions on individual firearm ownership or possession. For instance, most constitutional law textbooks either ignored the Second Amendment entirely or dismissed it with a short comment that it in no way protected any individual right or affected any gun control laws (perhaps dropping a footnote to United States v. Miller).

While there were occasional articles in what were perceived as “lesser” law reviews making arguments that have now been accepted as Second Amendment law, mainstream legal scholars at that time either ignored such articles or dismissed them as being written by cranks or NRA shills.

Perhaps due to this monolithic position in mainstream legal scholarship at the time, most courts (including all federal appellate courts) were unwilling to seriously entertain the argument that the Second Amendment protected any individual right.

Judges typically gave such arguments short shrift, treating them as they did arguments by pro se “sovereign citizens” that that paper money was not legal tender, that income taxes are unconstitutional, etc.

At that time there were serious proposals to ban most civilian ownership and possession of handguns (including by key members of the Carter administration). Indeed, the organization now known as the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence was then known the National Coalition to Ban Handguns, and the District of Columbia’s ban on handgun ownership that was struck down in Heller dates from this period. That such bans might be unconstitutional under the Second Amendment was simply not on the radar in most of polite academic society.

Don Kates

In 1983, attorney and criminologist Donald Kates published Handgun Prohibition and the Original Meaning of the Second Amendment in the Michigan Law Review, which examined the historical record (as well as the works of earlier legal scholars) and unabashedly argued that contrary to the near-universal academic view, the Second Amendment was indeed intended to protect an individual right.

While this was not Kates’ first article arguing that various gun control laws and proposals were unwise or unconstitutional (he had published earlier articles in the St. Louis University Law Journal and, amazingly, in the ACLU’s own Civil Liberties Review), this was the first article published in an “elite” law review that argued that the Second Amendment might actually mean what it says, and protects an individual right to keep and bear arms.

How was Kates able to break through and publish this argument in an “elite” journal while others had not? As you’ll see from his article, it is very well-written and researched (but then again, so were earlier works by scholars such as Stephen Halbrook, Robert Dowlut, and Janet Knoop, all of which Kates cited).

What Kates may have had going for him was that he could not simply be dismissed as a purported crank or NRA stooge. He was an accomplished lawyer, criminologist, and occasional law professor whose credentials as a liberal and civil liberties advocate could not be ignored.

And, perhaps, Kates’ willingness to allow for “reasonable” restrictions on the Second Amendment (e.g., at least at that time, he had no issue with prohibitions on carrying outside the home for self defense) distinguished him from what legal academia considered the “gun nuts” who advocated more absolutist interpretations.

While Kates’ article in the Michigan Law Review raised many eyebrows, it did not materially move the needle. Law treatises and textbooks – and the courts – largely continued to ignore or denigrate the Second Amendment throughout most of the 1980’s.

But the fact that the issue was starting to be taken seriously sparked conversations and interest in similar works of other scholars (such as Nelson Lund, Stephen Halbrook, and Joyce Lee Malcolm), as well as a reexamination of earlier works by authors such as Dowlut and Knoop. It also attracted the attention of another scholar who could not be ignored or easily dismissed.

Sanford Levinson

Sanford Levinson is a law professor and political scientist at the University of Texas. For decades, he has been regarded as one of the country’s leading constitutional theorists.

He is not a conservative, originalist, textualist, or a gun owner. Indeed, most of his positions are well left of center. However, even his critics respect him as a prolific scholar of impeccable academic integrity and intellectual honesty, someone willing to ask very difficult questions, do the hard work required to answer them, and let the chips fall where they fall where they may (as opposed to where you might want them to).

Disclaimer: he was one of my professors at UT Law in 1983. Later, when I was an Articles Editor on the Texas Law Review, he was one of my “go-to” resources on the UT faculty.

In the late 1980’s, Levinson turned his attention to the Second Amendment arguments that Kates and others were raising. What resulted was, in my opinion, perhaps the most influential article in Second Amendment jurisprudence: a 1989 Yale Law Journal article titled The Embarrassing Second Amendment which reprised a presentation Levinson had made at a constitutional law symposium in 1988.

Levinson acknowledged that legal academia, for a variety of reasons, had treated the Second Amendment like the crazy old uncle who is locked away in the attic and not spoken of in polite conversation.

I cannot help but suspect that the best explanation for the absence of the Second Amendment from the legal consciousness of the elite bar, including that component found in the legal academy, is derived from a mixture of sheer opposition to the idea of private ownership of guns and the perhaps subconscious fear that altogether plausible, perhaps even “winning,” interpretations of the Second Amendment would present real hurdles to those of us supporting prohibitory regulation. Thus the title of this essay–The Embarrassing Second Amendment–for I want to suggest that the Amendment may be profoundly embarrassing to many who both support such regulation and view themselves as committed to zealous adherence to the Bill of Rights (such as most members of the ACLU).

He posited that this failing was intellectually dishonest. That there were, in fact, good faith arguments that the Second Amendment protected some sort of individual right although, as will be discussed below, his conclusions of the scope of that right are quite different than most.

He concluded:

There is one further problem of no small import: if one does accept the plausibility of any of the arguments on behalf of a strong reading of the Second Amendment, but, nevertheless, rejects them in the name of social prudence and the present-day consequences produced by finicky adherence to earlier understandings, why do we not apply such consequentialist criteria to each and every part of the Bill of Rights? As Ronald Dworkin has argued, what it means to take rights seriously is that one will honor them even when there is significant social cost in doing so. If protecting freedom of speech, the rights of criminal defendants, or any other part of the Bill of Rights were always (or even most of the time) clearly costless to the society as a whole, it would truly be impossible to understand why they would be as controversial as they are. The very fact that there are often significant costs — criminals going free, oppressed groups having to hear viciously racist speech and so on — helps to account for the observed fact that those who view themselves as defenders of the Bill of Rights are generally antagonistic to prudential arguments. Most often, one finds them embracing versions of textual, historical, or doctrinal argument that dismiss as almost crass and vulgar any insistence that times might have changed and made too “expensive” the continued adherence to a given view. “Cost-benefit” analysis, rightly or wrongly, has come to be viewed as a “conservative” weapon to attack liberal rights. Yet one finds that the tables are strikingly turned when the Second Amendment comes into play. Here it is “conservatives” who argue in effect that social costs are irrelevant and “liberals” who argue for a notion of the “living Constitution” and “changed circumstances” that would have the practical consequence of removing any real bite from the Second Amendment. …

For too long, most members of the legal academy have treated the Second Amendment as the equivalent of an embarrassing relative, whose mention brings a quick change of subject to other, more respectable, family members. That will no longer do. It is time for the Second Amendment to enter full scale into the consciousness of the legal academy.

To be sure, Levinson was not arguing that the Second Amendment precluded any particular gun control measures. Indeed, he has long been in favor of various prohibitory regulations. That did not stop some lightweight critics from hysterically accusing Levinson of being an NRA stooge – an assertion that anyone with the slightest acquaintance with Prof. Levinson would know to be utterly preposterous. But there is no question that this article — by a leading constitutional theorist, published in one of the very top law reviews — provoked a huge reaction.

All manner of law professors began publishing articles supporting or disagreeing with Levinson, which were also published in other “elite” law reviews including the Yale Law Journal. These in turn sparked many more articles — including more by Kates and Levinson — symposia, panels, and papers, as legal academia began the robust debate Levinson envisioned on the Second Amendment and what it means.

Levinson’s article also led even hardcore Second Amendment skeptics such as Harvard’s Laurence Tribe to amend their constitutional law textbooks and treatises to acknowledge that there were serious arguments as to whether the Second Amendment protected any individual right.

Thus, as a direct result of Kates and Levinson legitimizing debate about the Second Amendment in polite academic society, there was an avalanche of Second Amendment scholarship in the 1990s, including influential works by scholars such as Akhil Amar, Elaine Scarry, James Ely, Lucas Powe, Glenn Reynolds, Robert Cottrol, Eugene Volokh, Randy Barnett, David Kopel, and many others.

This debate convinced some scholars such as Daniel Polsby, who had previously considered the individual rights interpretation of the Second Amendment to be “a lot of horse dung,” to recant and admit that:

[A]lmost all the qualified historians and constitutional-law scholars who have studied the subject [concur]. The overwhelming weight of authority affirms that the Second Amendment establishes an individual right to bear arms, which is not dependent upon joining something like the National Guard.

This tide of scholarship – which in a few years time turned the individual rights view of the Second Amendment from heresy into gospel – in turn helped influence courts to reexamine their views of the Second Amendment, which ultimately resulted in Heller and now Bruen.

A few days after the Bruen opinion dropped, I was able to interview Prof. Levinson about his reactions to the decision.

On one hand, he does support the procedural result of Bruen. He sees the discretionary New York permit process as arbitrary, flawed, and favoring the well-connected, and thus could have been invalidated any number of ways. He also believes that Heller and Bruen were correct to find that there is a constitutional right to self defense, and such a right could invalidate some (but by no means all) prohibitionist laws.

However, Levinson would get there by finding such a right in the Ninth Amendment and the privileges and immunities clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, rather than in the Second Amendment. His interpretation of the Second Amendment is that it protects “civic republicanism,” that is, the right of the people to have arms in order to resist tyranny, although he admits that view is not one most judges would be comfortable espousing.

On the other, he vehemently disagrees with the language and reasoning of Bruen, indicating that Justice Thomas’ opinion “pours gasoline on the culture wars.”

He criticizes the Court’s “insane embrace” of 1791 originalism and its reading of the applicable history, especially in light of his view that justices are “wildly unreliable as historical narrators.” The Court’s opinion has created “its own version of the Second Amendment,” which he sees as “fictitious” and “radical.” He views Second Amendment literalism as a “looney view” of the Constitution.

Given that his 1989 Yale Law Journal article helped start the avalanche of Second Amendment scholarship that has now culminated in this “radical” decision, I asked if he has any regrets about writing it. “My friends have asked me that a lot,” he replied, but “no, for two reasons.”

First, he says the purpose of scholarship “is to get things right.” Ignoring questions about a constitutional provision because you are afraid of the possible answers is “a scandal,” and the Second Amendment is an interesting issue that deserves serious study. And he stands by his “civic republicanism” thesis: that the reason for the Second Amendment is to protect the right of the people to have arms in order to resist tyranny.

Second, he sees his views on the Second Amendment as rooted in political reality. At the time he wrote it, Democrats had “overindulged in symbolic gun control” that needlessly alienated gun owners. Because many gun owners are single-issue voters, that had the effect of creating many Reagan Democrats, and that has forced a political realignment that might not have happened had the Democrats “shown more genuine respect” for gun owners.

People of all political stripes have disagreed with Prof. Levinson’s views on constitutional law for decades. As an originalist, I disagree with many of them. But unlike so many in academia today, Levinson has never shied away from difficult issues because the debate or the answers might be “triggering,” politically inconvenient, or contrary to the prevailing narrative.

Indeed, he sees grappling with such issues as the fundamental role of a scholar. Whether you agree or disagree with Levinson’s views or his conclusions, his honest challenge to the legal academy was a key catalyst in the development of today’s Second Amendment law.

How would Don Kates (who passed away in 2016) have reacted to Bruen? I asked University of Tennessee law professor Glenn Reynolds (a/k/a Instapundit), who collaborated with Kates on Second Amendment articles, and he responded:

I believe that Don would view the Bruen decision as largely correct. Though much of his scholarship was focused on what Sandy Levinson calls the civic republican aspect of arms-bearing, Kates also argued that self-defense was a fundamental right. Indeed, as he pointed out in a Constitutional Commentary article, “The Second Amendment and the Ideology of Self-Protection,” the framers didn’t draw much of a distinction between ordinary burglars, robbers, and murderers and a tyrannical government. To the framers, action outside of legal authority was just as criminal when engaged in by government officials and employees as when engaged in by ordinary criminals.

Neither Kates’ nor Levinson’s articles espoused Second Amendment absolutism. Both viewed various restrictions on gun ownership as constitutionally acceptable, including many that will likely not survive under the Bruen test.

But both of these scholars had the courage to call out legal academia for its intellectual laziness, if not its cowardice in failing to address the Second Amendment. That they helped start the conversation in legal academia that led to the Second Amendment being taken seriously deserves our recognition and our appreciation.