If it hadn’t been for B. Tyler Henry and his rifle design, O. F. Winchester and his rifle might not have become the iconic firearm that it is today.

When Henry patented his new rifle in October 1860, he couldn’t have known the ripple effect that his gun would have. Though it took until July 1862 to get guns produced and ready for sale, they were a hit with the men who got to try one out. Soldiers fighting our bloody Civil War saw the advantage of this repeater.

S. Curtiss, Major of the 1st Maine Cavalry, said the Henry was “far superior in all respects” and that he “would by no means use any other [rifle] if it could possibly be procured.” Major Ludlow of the U.S. Corps of Engineers was equally enthusiastic. Speaking about the 1864 battle of Allatoona Pass, he said ,“[w]hat saved us that day was the fact that we had a number of Henry rifles,” adding that the rapid fire produced by the rifles was something that “no man could stand in front of.”

Military brass, however, saw things differently. Not only were Henry rifles more expensive to purchase than their muzzleloading counterparts ($42 each compared to $20 for a Model 1861 muzzleloader), their rapid firepower caused some officials to fear that soldiers would waste ammo if they could fire it faster. A soldier was more likely to make a well-aimed shot if he could only fire the gun three times a minute, they reasoned.

Despite the fact that Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, and President Abraham Lincoln himself all owned Henry rifles, they were never adopted as a standard issue firearm. (Interestingly, Secretary Stanton got serial number 1; President Lincoln got serial number 6.) Only 1,731 rifles were actually purchased by the United States. Even so, many units purchased them privately and used them with great effectiveness in the field. The 7th Illinois Infantry is known to have carried Henry rifles. They even posed for a group photo, complete with their flag and their Henry rifles.

Henry rifles were also made with iron frames, but in much smaller numbers. Believed to have been made in hopes of securing a contract with the U.S. Navy, production stopped when no such contract materialized. As such, the total production of iron frame Henry rifles sits at around 300 units, making them highly collectible today.

Henry’s rifle was only in production for a brief period of time. Despite its ingenuity, the gun had some drawbacks. Chief among them was the loading mechanism, which had an external sleeve that rotated out at the muzzle to allow rounds to enter the magazine tube located directly under the barrel. The brass follower worked its way from the muzzle toward the receiver with each round fired, which meant that a poorly placed hand could prevent the gun from cycling. A lack of hand guard – because of the follower – also meant that the shooter could burn their hand on the barrel when the gun was fired rapidly.

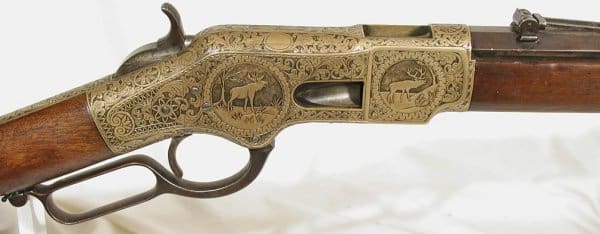

By 1866, production on Henry’s rifle came to an end with only 14,000 having been produced. The gun didn’t disappear entirely, though. A similar rifle featuring a hand guard and loading gate designed by Nelson King entered the market that same year under a new name: Winchester’s Model 1866.

It would be Winchester’s 1866 that paved the way for the most iconic lever action rifles of all time. Their Model 1873 is probably one of the most recognizable long guns known the world over. Now celebrating their 150th anniversary, Winchester owes a debt of gratitude to Benjamin Tyler Henry and his rifle.

Logan Metesh is a firearms historian and consultant who runs High Caliber History LLC. Click here for a free 3-page download with tips about caring for your antique and collectible firearms.

Winchester might owe the early success to Henry but the great majority of their success was due to the brilliance of John Browning. John Browning didn’t invent a rifle, he invented rifles, pistols and machine guns. He sold many of his designs to Winchester but they didn’t make many of them but bought them to keep then away from the competition.

All true. This month’s American Rifleman has a great article on Winchester and talks about Henry’s contribution. Lever action rifles like the Winchester, Henry and Marlin are uniquely American and I have a faithful Marlin 30-30 in my emergency stash. These are great guns for prepping or just for general use. You can put rifle caliber rounds downrange at a decent rate of fire, reload on the fly, and the 30-30 is very comparable to the 7.62X39 round in pretty much every way. Finally, if they ever do succeed in outlawing detachable magazine rifles, the lever action will still be around.

Yeah, let’s statutorily return to the 19th Century.

Twitter is the “assault weapon” of the 1st Amendment.

It’s a little more complicated than this article would suggest. Winchester, a successful business man, bought out the volcanic arms company, which had folks like Smith and Wesson involved. If you see a photo of a volcanic arms pistol it screams Henry and proto type Winchester at you.

The biggest weakness of the Volcanic was it’s ammo. Most guns were front loaders at this time and the volcanic was an attempt at a repeating firearm with self contained ammo. The ammo sucked and people stayed away in droves.

Henry worked for Winchester, who had at least one factory at the time. Winchester dropped the volcanic and it’s ammo on Henry’s desk and asked him what could be done about the pistol.

In the process of correcting the faults of the volcanic pistol Henry turned it into a rifle and starting from scratch he designed the .44 henry rimfire ammo.

In the civil war the Spencer was much more successsfull, with something like 90k being purchased by the union army. Several other carbines bought by the ever gun hungry Union were chambered in the Spencer round just to provide some ammo commonality in supply.

“Henry rifles were also made with iron frames, but in much smaller numbers. Believed to have been made in hopes of securing a contract with the U.S. Navy,…”

Now that’s interesting.

I would think in a saltwater environ, brass would be far superior to corrosion-prone iron.

Or am I missing something obvious?

I was kind of wondering that myself.

Brass doesn’t hold up in salt water. Believe it or not, iron holds up better than brass in those conditions.

H’mmm.

Marine propellers are made of bronze, a copper-tin alloy, while brass, a copper-tin mix is supposedly more malleable. But I’m no metallurgist…

I wish modern Henrys had a loading gate.

Ideally. Although my Big Boy 357 is so dang beautiful and fun, I can forgive them.

Owes or owed?

there’s this, ya’ll

winchester ’73: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-D5_0cMzFVw

fun ta watch, an’ some familiar faces when they were lots younger, and rock hudson as an indian war chief.

Don’t forget the era. Schofield, Spencer, Martini, Mauser, Remington, Colt; were all making big strides in ballistics and platforms to make them shoot bigger better faster.

Browning, Maxim, Garand soon followed.

Amazing moment in firearm history.

And don’t forget the likes of Dreyse, Mondragon, and Lee. And of course the many French designers whose main limitation was their government who never seemed to make up their mind besides to screw a good design up.

Yes, I know this is necro-posting but this historical ignorance needs correcting.

The Winchester Model of 1866 is a direct descendant of Walter Hunt’s Volitional repeating rifle. And popular myth notwithstanding, Benjamin Tyler Henry DID NOT invent it.

Walter Hunt invented his lever gun no later than 1847 but its feeding mechanism was flaky and his bespoke cartridge was anemic. Hunt paid George Arrowsmith to manufacture a few, but Arrowsmith had Lewis Jennings knock off a few rough edges first.

Jennings and Arrowsmith soon deemed the design beyond their financial means to put right so Arrowsmith sold the improved Jennings-Hunt magazine rifle (with Jenning’s 1849 patent) to Courtlandt Palmer.

Palmer hired gun makers Robbins & Lawrence to build the rifle, but those didn’t function well and weren’t selling so Palmer hired Horace Smith to make improvements. R&L made about 1100 copies of Smith’s three successive versions of the rifle (now called the Smith-Jennings) before the company went bust after defaulting on a contract to make rifles for the British.

Daniel Wesson had been working at the Robbins & Lawrence factory as an inspector for Leonard Pistol Works, which was buying parts from R&L. In that time he had become familiar with the Smith-Jennings rifle and after the factory was shuttered, he and Horace Smith agreed to form a company to further develop it.

One year on, the Smith & Wesson Company took on investors, including Oliver Winchester. Renamed the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company, they lasted a further two hears before going bankrupt.

Smith and Wesson decided to remain a team and to go into the revolver business. Oliver Winchester, who had been loaning the faltering company money, convinced the bankruptcy court that he alone among all the investors deserved to get the entirely of the company’s holdings. The other investors got shown the door.

Winchester moved the company to Connecticut and renamed it New Haven Arms Company. B.T. Henry made the move with Winchester, continuing to refine the Smith-Jennings Volcanic rifle and inventing the metallic cartridge that put the rifle on the map, the rimfire .44 Henry.

At this juncture you also have to factor in the significance of the War Between the States. From a historical perspective, it’s impossible to say to any certainty whether the Winchester Arms Company would have survived or died on the vine without the coincidence of the American Civil War starting just as the Henry rifle came available (patented just seven months before Ft Sumter). In fact, considering how many half-assed arms companies had their lives extended by the war (i.e., Evans, and Spencer), one might argue it was THE most important factor.

So claiming Henry made Winchester gives the short shrift to the genius (or financial support) of Walter Hunt, George Arrowsmith, Lewis Jennings, Courtlandt Palmer, Robbins & Lawrence, Horace Smith, Daniel Wesson, and Prince Albert (whose 1851 exposition got Robbins & Lawrence in bed with the British Army).

The war aside, remove any one link from that chain and Henry would have never so much as seen the Volcanic rifle to begin with, much less been gifted one to do development on.

And take away Mr. Lincoln’s war and Winchester Arms might well have failed and Oliver might have gone back into making bloomers and drawers.

And then there’s the small matter of B.T. Henry’s attempt to steal the New Haven Arms Company from Oliver.

In 1864, with the full knowledge that Oliver Winchester was out of the country and unable to defend his interests, Henry approached the Connecticut state legislature with the claim that Winchester had not fairly compensated him for his contributions to the company’s success, and asking that he be awarded it sole ownership.

Somehow Winchester’s factors in the US managed to get in touch with him in Europe, tell him what Henry was up to, and he got home in time to forestall Tyler’s action. That was what prompted Winchester to rename the company after himself. And obviously he gave Benjamin Tyler Henry his walking papers.

So, in truth, the man you claim “made” Oliver Winchester did his damnedest to destroy him.

I think it’s a sad state that that’s not the story that comes to mind whenever people hear the name of Benjamin Tyler Henry, instead of the absolute LIE that he “invented” the lever-action rifle.

Comments are closed.