Shootings suck. That’s a fact that everyone of every political color can agree on. The world would be a much better place if people didn’t shoot at each other and only pieces of paper had to be worried about flying bullets. In the search for a way to uniquely tie an individual to a crime scene, one idea that has been getting some traction (as seen on today’s Boston.com site, which prodded me into finally writing this) is microstamping. So, what exactly is this wonder technology and does it really work? Here’s the truth…

With most firearms in the world, once a round has been fired the firearm kicks it out of the gun and leaves it lying on the floor. Just about every type of gun, from lever action to bolt action to semi-auto pistols, discards the spent casing when it no longer has a use for it. It makes sense — it saves space, decreases weight, and allows for faster reloading. It also means that when someone uses such a firearm in a crime, typically the criminal will leave the spent casings lying on the ground.

Cases, along with the bullets also left behind by the shooter (usually in victims or walls, though), can sometimes tie a firearm to a specific crime scene. The marks left on the bullet by the barrel of the firearm are like a fingerprint, but much more likely to be smudged and deformed when the bullet eventually hits something. Cases also have identifying characteristics, such as the impression the firing pin makes in the primer and the impression the breech face makes on the case head. The only problem with using these features to identify a firearm is that (a) you need an example of a fired case and bullet from the firearm in question to do the comparison and (b) these characteristics can change wildly as parts are replaced or worn down. A bullet fired from a new gun and one fired from that same gun 1,000 rounds later don’t tend to match very well.

So what’s something that never changes and can uniquely identify a firearm even if you’ve never seen it before? A serial number.

In theory it makes perfect sense. If all guns left a serial number on the cases they fired, then spent cases can be tied to firearms and firearms can be traced back to owners. That is, if it works and if it’s reliable.

Unfortunately, as it stands now microstamping isn’t really a viable technology. There are about five major drawbacks and plot holes that need to be addressed before it’s really ready for mandatory use.

Drawback #1: Stamps Wear Out and Disappear

Ever heard the old adage “the nail that sticks up gets hammered down?” The chamber of a firearm works in a similar manner. As you fire the gun the chamber and associated parts are subjected to immense levels of pressure and friction. This pressure is so great that on my SIG SAUER pistol there’s actually the impression of a 9mm case head worn into my bolt face (to be fair, it’s seen about 5k rounds per year with me and I’m the third owner).

If the pressure and friction of normal operation can do that to a solid and uniform piece of metal, think about what it will do to a set of raised letters. As the Law Enforcement Alliance of America puts it, “…decades of forensic science with firearms clearly demonstrate that marks left […] by the internal parts of a firearm change dramatically with normal wear.” Even if the stamp is bright and clear on round number 1, what will it look like on round 6,435?

Anywhere you put a stamp in the chamber of a gun it’s easy to wear away or be removed. Stamps on the breech face can be filed off. Stamps on firing pins can be filed off or removed by changing the firing pin (or worn off with normal wear, given the extreme pressures subjected to the firing pin). And stamps on the inside of the chamber will probably be sheared off in a few short rounds due to the friction. There’s no safe place to put it.

Drawback #2: Revolvers and Polite Criminals

Microstamping is a great theory for semi-automatic firearms, but what about revolvers?

Revolvers are the more polite type of firearm. While other guns just spit their spent casings everywhere revolvers retain those casings and keep them with the gun until the shooter wants to reload. So instead of a crime scene littered with finely stamped casings now there’s nothing, unless the criminal is dumb enough to empty the revolver at the crime scene. Then again, criminals are pretty dumb to begin with.

This is actually a pretty large concern, as the ATF notes SSmith & Wesson .38 Special revolvers as the typical firearm of choice for criminals. Then again, the latest report I could find is from 2000.

The point I’m trying to make is that in order for microstamping to be effective, the shells have to be left behind. Whether it’s a revolver, a plastic bag over the gun, or even just a criminal that takes the time to police their brass, it only takes a little bit of effort to deprive the police of the evidence that microstamping would have provided.

Drawback #3: Registered Owner or Shooter?

There have been a couple gigantic lawsuits in the last few years where motion picture companies have been suing everyone who illegally downloaded their movie. The problem with these lawsuits has been that the motion picture companies don’t provide names, they provide IP addresses. An IP address is like your street address — it tells computers on the internet where to send the data you want. IP addresses do not, however, identify the person behind the keyboard requesting the data, or even which specific computer if it’s a home network.

This lack of specificity has led to a number of these monster cases being thrown out or dropped. According to the EFF, an IP address is not enough information to uniquely identify a person.

Sound similar to what we’re discussing? Let’s apply this in context.

Let’s suppose that microstamping works. A criminal uses a microstamping firearm, doesn’t clean up after themselves, and leaves a perfectly impressioned case at a crime scene. In this fantasy world, all the police would have to do is get the ATF to track the serial number back through the FFLs and arrest the guy holding the last form 4473, right? Wrong.

There can be a number of legitimate reasons why the last 4473 form doesn’t have the current owner’s name on it. Private party transfers is the first one that pops into mind (that pesky “gun show loophole”), but the gun could have easily been a gift or willed to someone else as well. There are even bigger illegitimate reasons, such as the gun being stolen or “lost” and then found by a less upstanding member of society.

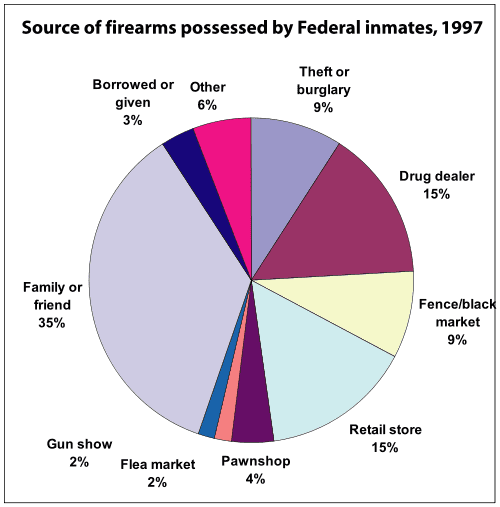

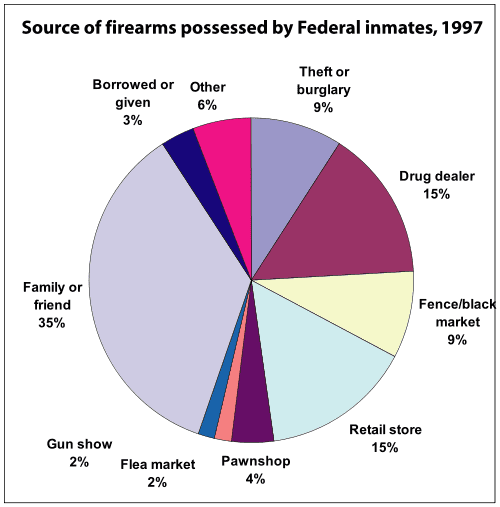

According to a 1997 study of Federal inmates by the Department of Justice, only 15% of criminals obtained their guns from a retail store. That means only 15% of firearms used by criminals can (in theory, at least) be traced to the criminal themselves on the 4473 form by the ATF. The remaining 85% of guns will trace back to someone else.

(Just FYI, the “Family or friend” category does not mean the gun was legally possessed by the family member or friend in question, and so would not necessarily trace back to them either.)

Long story short, just as the MPAA now understands, a unique ID number isn’t always as unique or as identifiable as you think.

Drawback #4: Salt

This last one is for the more paranoid among us.

It’s a dark and stormy night. Two shadowy figures walk into a dark alleyway. Suddenly, gunshots erupt in the inky blackness sending streaks of light bolting from the darkness. One of the shadowy figures drops to the ground, the other one stands over them with a revolver. Before the shadowy figure leaves they open a bag of spent casings they picked up at the gun range where Joe Citizen, an upstanding member of society, has been legally practicing with his firearm, and sprinkle the casings around the corpse.

The next day, after the police trace the stamped cases back to Joe Citizen’s gun, he’s arrested in front of his family, charged with murder, and perp walked on national television. Joe Citizen’s life is pretty well and truly screwed.

The scenario above is completely plausible. And while the mistake may be eventually realized and an apology issued, in an age where that one picture of you playing beer pong in college can disqualify you from a job I’m pretty sure a Google result with your name and “murder” in the same sentence isn’t good.

Drawback #5: A booming used gun market

Even if microstamping is mandated by law, works like a charm, and always indicates the right shooter, there’s always going to be a used gun available from an era before microstamping. Always.

There are millions of firearms in the United States. Millions. They’re everywhere. Finding and destroying every single one would take decades of police work and billions of dollars. Not gunna happen.

Even after a lengthy campaign against previously legal guns, they will still be available. Let’s take England as a case study. Firearms have been illegal (except for the permitted chosen few) for many decades. And yet, illegal firearms seem to keep popping up in the hands of criminals. No matter how hard the government cracks down, firearms will still be available to the determined criminal.

So what’s the bottom line?

It’s not gunna work. Not right now, at least.

There is an argument to be made about “dumb” criminals failing to remove the microstamp from their firearms, but statistically speaking that wouldn’t matter. Even if the stamp is in place, according to the DoJ 85% of firearms are illegally obtained. That means that there would be no available records to tie the shooter to the gun.

Right now, the only effect that microstamping would have on firearms is raising the price and inconveniencing law abiding citizens. That’s not a “minor” inconvenience either, especially when the possibility of being wrongly accused for a murder is only one lazy range trip away.

I would LOVE a foolproof way to catch criminals. The second you show me one I’ll be the first person championing it. But with this method, it’s just as likely to implicate innocent people, not rugged enough to survive normal wear and tear, easy to defeat, and makes the guns more expensive to manufacture.

In short: it sucks. And that’s not just my professional opinion, that’s a fact.