Boston Corbett stood ready, Colt 1860 Army revolver in hand, and had a split-second decision to make that would determine whether his fellow troopers would live or die. After a lifetime of sin, he would be the one to render judgement. It was a long climb up after finding religion and his way into the Union Army at the outbreak of the Civil War. War’s end found Sgt. Corbett and the men of the 16th New York Cavalry Regiment in Northern Virginia. But within days of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, the 16th was put on high alert and sent to patrol the countryside, milling around roads teaming with civilians and paroled rebel troops in search of one man.

That search came to an end in the early morning hours of the 26th of April 1865, with their target held up in an old tobacco barn. The man they were seeking was John Wilkes Booth, the great thespian who had been on the run for 12 days after assassinating President Abraham Lincoln. Booth was joined by co-conspirator, David Herold.

With torches lit and pistols drawn, the 16th New York surrounded the barn and demanded Booth’s surrender. As flames consumed the structure, Booth allowed Herold to give himself up. But Booth himself was prepared to shoot his way out. Through slats between the boarded walls of the barn, silhouetted against the glare of the flames, Boston Corbett saw Booth drop his crutch and raise a Spencer carbine. In that moment, Corbett leveled his pistol between the slats and fired.

Booth dropped to the ground and was dragged out of the barn. Booth died several hours later from a shot through the neck, which had severed his spine. Corbett claimed he intended to disarm Booth with a shot to the arm, but he had made previous statements about wanting to avenge the fallen president.

As what had marked the final hours of Lincoln’s life, souvenir hunters stalked the 16th for any tangible piece to history in the making. Pages from Booth’s diary went missing. In a matter of days, Corbett’s Colt 1860 Army revolver also disappeared, but it likely was not missed.

Colt’s 1860 Army revolver, otherwise known as the New Army revolver, was the most common sidearm issued during the American Civil War. The U.S. Cavalry adopted it readily in 1860 and it remained the Army’s standard issue handgun until it was replaced by the famous Colt Peacemaker in 1873. It never gained the sales status of the earlier Colt 1851 Navy model, and it lives permanently in the shadow of its successor. I always preferred the Navy, but I decided to purchase a new Cimarron Colt 1860 to see if I could be persuaded.

How the U.S. Army Arrived at the Colt 1860

In the mid 1850s, Samuel Colt and the Colt Manufacturing Company were facing the problems of aging designs and an expiring patent that enabled competition in a market Colt had created from the ground up. Colt invented his first revolver in 1835 and after the Mexican War, the U.S. Army was a reliable buyer of .44-caliber revolvers.

The .44 caliber was deemed powerful enough to stop a horse at 75 yards, while the smaller .36-caliber guns proved lacking. Unfortunately, the .36-caliber Colt 1851 Navy was light enough to carry on a belt. The existing .44-caliber Walker and Dragoon pistols were designed to be carried in holsters on a horse.

Colt spent the 1850s trying to cut down the Dragoon, when a solution was found to simply upscale the Navy. The Colt 1860 Army model that handily won the cavalry trials that year featured a Navy frame and internal lock work, but the cylinder frame is relieved for a flared cylinder that could accommodate six rounds of .44.

The hinged loading lever and octagonal barrel of the Navy were switched for a lighter and more economical rack and pinion loading lever and an 8-inch round barrel. The Colt 1860 was also made of the latest silver steel alloys made possible by the new Bessimer process that made steel production cheaper. Although Colt had issues getting the new alloy initially, the final product was as light and pointable as the Navy but was stronger and had the hitting power the Army wanted.

The first Colt 1860 revolvers hit arsenal shelves on both sides of the Mason Dixon line just as the secession crisis reached its fever pitch. Ultimately, more than 127,000 units were delivered to the Union Army before a fire put Colt’s plant out of commission for the duration of the war. By the end of its total production run in 1873, over 200,000 were made, making it an everyman’s gun in its own time. Samuel Colt, however, would not live to see it as he died in January 1862, making the Colt New Line the last handguns Colt himself worked on. But his last revolver would be the mainstay of the Union through the Civil War and see the post-war Army through until the Colt Peacemaker was adopted in 1873 at the height of the Indian Wars.

Cimarron’s Colt 1860 Army Revolver

Cimarron calls their Colt 1860 Army revolver a “civilian” model because of its brass trigger guard and grip frame, but most 1860s have this. But the casehardened loading lever and cylinder frame, as well as the laser engraving on the blued cylinder are refinements you likely won’t find on military contract handguns.

Otherwise, Cimarron’s 1860 is functionally identical to an original down to the size and shaping of the lock work up to the basic features. It wears a one-piece walnut grip that is similar in shape to the Navy’s grip, but longer for bigger hands. The 1860 features an 8-inch round barrel with a fixed brass front sight to pair with a rear sight that consists of a notch in the hammer face.

Like most Colt cap and ball revolvers, it is an open top design and uses a captive wedge to retain the barrel or remove it for cleaning. The 1860 is a single-action revolver and is a six-shot .44-caliber revolver. There is no safety on the 1860 except for a set of pins that allow you to safely lower the hammer in between cylinders so you can carry the revolver fully loaded.

Historically, Colt converted some of their 1860s to fire .44 Colt cartridges in the 1870s, but almost all originals and replicas, including this one, is in the original percussion configuration that requires powder and ball to be loaded from the front of the cylinder and percussion caps installed from the back. As it happens, Kirst and Howell produce ready-made conversion cylinders to shoot .45 Colt ammunition.

Quick Specs

- Model: 1860 Army

- Caliber: .44

- Capacity: 6

- Barrel Length: 8 in.

- Overall Length: 13¾ in.

- Weight: 2 lbs., 11 oz. (unloaded)

Loading the Colt 1860

Cap and ball revolver replicas tend to come out of the box as a kit gun in more ways than one. Although finished and ready to shoot, many require some minor work or modifications to run smoothly and reliably. But Cimarron seems to vet the revolvers that come in. Out of two Cimarron 1860s I’ve owned, neither required work to get onto the range. This particular 1860 has gone over two hundred rounds with sparce cleaning and no malfunctions of any kind. But shooting percussion revolvers is just as much of the journey to that round count than the end result.

Percussion revolvers were generally sighted to hit to the point of aim at 75 yards. But for most of us, we will be shooting at much closer ranges so, these revolvers tend to shoot quite high. After taking some offhand shots to get reacquainted, I set up a target at 20 yards and settled in at the bench to put the gun on paper.

The U.S. Army loaded the 1860 almost exclusively with combustible paper cartridges that included powder and bullet in one package that was rammed wholesale into the chamber. But just about all of these replicas require the loading port under the loading lever to load in such a way. So, I loaded like most modern shooters do, with loose powder and ball.

Loading starts by thumbing the hammer to half-cock so the cylinder will spin for loading. Then you can introduce a measure of powder, followed by the bullet. Rotate the bullet under the loading lever and push it home. If you plan to shoot much or are going for best accuracy, some grease over the bullet or a wad between bullet and powder will help keep the fouling soft for prolonged shooting. With the cylinder loaded, you can then place a percussion cap on the cones, or nipples, at the back of the cylinder. With all that out of the way, you can shoot.

On the Range

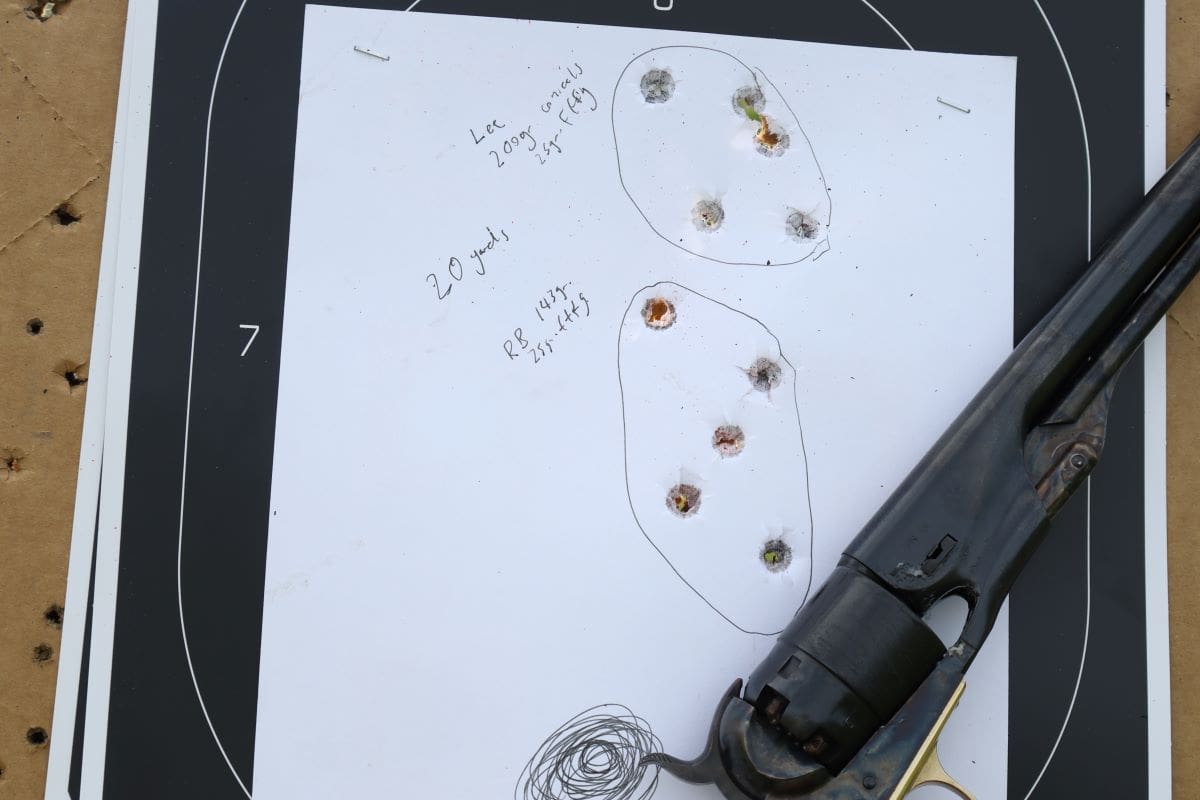

I shot my first group using 25 grains of FFFg blackpowder and a 143-grain .454-inch round ball. The balls were easy and fast to load and recoil was minimal, although there was plenty of smoke. I put five rounds into a 3-inch cluster about 4 inches above my point of aim. Using the same charge, I switched over to a cast 200-grain Lee conical bullet. These longer bullets had to be started into the chamber mouths, but otherwise seated just as easily. Recoil was more pronounced and these heavier bullets struck about 8 inches high, but all within a respectable 2-inch group. Both loads also shot about an inch and a half to my right. This is close, which is fortunate because there is no way to adjust the sights for windage.

I later upped my powder charge to 30 grains, which is the prescribed Army load using a conical bullet. I shot the round ball and conical over my chronograph and got an average velocity of 764 feet per second with the round ball and 728 feet per second with the conical. Although there was a gain in power, my groups and accuracy with both rounds inverted. Still, a six-o’clock hold on any target gave me a hit as started shooting offhand. Whether I was shooting 8-inch plates at 10 yards or ½ size steel silhouettes at 35, the hits came easy as long as I remembered my hold.

The sights are low profile, but finding the front brass blade is easy enough to do quickly, although lining it up with the rear notch does take an additional split second. Fortunately, the 1860 is one of the more balanced guns Colt made, and it points like a finger would. The trigger, although thin at the shoe, was light, breaking at just over 3 pounds. All of this combined to make the 1860 a more shootable gun than it ought to be by modern standards.

The Colt 1860 Army Revolver: An Underrated Six Shooter

The Colt 1860 Army revolver was a paradox of its time. It represents the pinnacle of Colt’s cap and ball revolvers alongside the Colt 1861 Navy and 1862 Pocket Police that came out in the same year. It took advantage of the latest steels and was wholeheartedly adopted by the Cavalry. But it lacked the solid frame that modern shooters have since become familiar with on the contemporary Remington New Model Army and the Colt 1873. It was also a percussion revolver adopted just as cartridge handguns were coming onto the scene.

Still, it served hero and villain alike amongst those who could get one and keep one from the earliest days of the Civil War for decades onward, well after the cartridge gun became truly viable. It was safe to carry with all six rounds loaded, had the perfect power to size ratio and was as pointable as a finger—and it still is. Although an authentic cartridge conversion might deliver a lot of the satisfaction, when it comes to reliving the Civil War shooting experience, there is nothing quite like a Colt 1860, and Cimarron is bringing an excellent one to our mitts.

My understanding is that Colt designed the pistol for 35 grains of powder, but the Army found most of its soldiers could not handled the recoil even with the larger grips, and ordered that pre-made cartridges hold 30 grains. I’ve read that shooters of these modern replicas find that the 30 grain load is more accurate. Finally, you can lower the point of aim by cutting the hammer notch deeper.

I wonder if Trooper Snuffy Smith had to tweak his new Colt when it was issued to get it to run right?

Why are we moderns willing to spend money on new from the factory guns that then have to be fixed to work the way they were supposed to work?

The tweaking required requires the disassembly of the pistol–which, having only ten screws, was made to be disassembled–dulling the edge interfaces between the frame and the edges of the hammer, and polishing the faces of the round part at the bottom of the hammer so that it operates smoothly.

Unless a firearm is a signed custom build expect to tweak most assembly line firearms. The tweaking process is where a lot of ideas for aftermarket products originate. I.E…A spring may need to be made stiffer or weaker, a plastic component needs to be redesigned and made of steel, etc. For a large part tweaking most bread and butter firearms and mags involves dismantling, locating and eliminating friction points, tightening loose fitting components, proper cleaning, lubing, etc.

How it’s done…

https://youtube.com/shorts/5dm2f7Ms4hQ?feature=shared

Secession, not succession.

Ruger Old Army. Sob!

I never owned one. But friends did. I was able to shoot them quite a bit.

Nothing but good.

or just get an 1858 Remington

1860 less likely to jam, imo.

I thought I would like an 1858 until I picked one up. It hurts to hold it.

The Colt handle/trigger geometry is much more natural/comfortable to me.

“Boston Corbett”? Really “Boston Corbett”? Are we here at TTAG now celebrating Democrats who literally self-castrated themselves? Boston Corbett was a homicidal mentally disturbed Lib/Prog, and a 19th Century t®@nn¥, his image should be front and center each “Pride(pox) Month to remind the public what kind of deviants inhabit the “Rainbow” community.

Wrong on so many points. Boston Corbett lost his young wife (F) to illness, and became despondent. He took the Bible literally about “If thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out”, and decided to self-castrate in order to avoid the temptation of dishonoring the memory of his wife through debauchery. He was a talented hatmaker, but he was deeply religious to the point of fanaticism. He would take frequent breaks to pray for his coworkers who he deemed sinful, thus provoking their ire and shortening his employment at several milliners. Yes, he was crazy, but he was also crazily brave. He distinguished himself on the battlefield several times, but was often disciplined for insubordination. At one point he was sentenced to be shot, but they discharged him instead. He just reenlisted with a different outfit, the same one he was serving under when he shot Booth. In his day, Republicans were the abolitionist party, and Democrats were more likely to be sympathetic to slavery. He was staunchly abolitionist, so if he had any political leanings at all he was most likely Republican. There were no clear orders about whether or not Booth was to be taken alive, and the shooting was regarded as justified because Booth had allegedly raised a carbine. If Corbett were alive today, he would most definitely not be LGBTQ friendly due to his fanaticism. He disappeared in 1888 after escaping from an insane asylum.

It was common for hatmakers to go insane, why, because they used mercury when processing beaver (a typical material used for hats), the ground in certain cities in Connecticut (predominantly New Haven IIRC) are contaminated with the stuff, many processed the pelts in vats/pots in their backyards of homes so the soil there is rife with the stuff. As for Corbett being an “abolitionist”, they were a fanatical and homicidal bunch akin to today’s AntiFa (see “John Brown” and his murderous offspring).

Back in the day, an abolitionist could be mellow, murderous, or anything in between.

I had a black powder revolver and really liked it until I shot a Cottonwood tree across the river and the bullet bounced back and hit the dirt about an inch from my foot. I said ” I don’t like this anymore.”

P.S. to OP: The red stain was on the originals from Colt, which is why it is on the Ubertis.

I water proofed my BP revolver by letting candle wax drip on the primer once it was seated. At one time my edc was an 1851Navy and it did fail once due to moisture. By dripping candle wax on the percussion cap once it was seated on the nipple that problem stopped.

Chick-fil-A sandwiches are a fast-food favorite renowned for their simplicity and flavor. The classic Chick-fil-A Chicken Sandwich features a perfectly seasoned and breaded chicken breast, fried to golden perfection, nestled between a soft, buttered bun. A couple of crisp pickle slices add a touch of tangy crunch, creating a satisfying contrast to the tender chicken. The simplicity of the sandwich belies its deliciousness, with each bite offering a balance of textures and flavors that has garnered a loyal following

“Rotate the bullet under the loading lever and push it home.”

All the way to the powder. No air-gap between the ball and the powder.

I used to put candle wax on the percussion caps once they were seated on the nyple to keep the moisture out. Helps to prevent misfires.

Only issue I’ve had with percussion revolvers is the caps can and occasionally do drop off the nipple after being fired, thus preventing the cylinder from turning to the next chamber.

Simple fix is to do as was common practice for the soldiers and shootists of the time and raise the muzzle between shots while cocking the revolver.

I’ve heard of and read about chain fire etc but in the thousands of rounds I’ve fired in such weapons I’ve never had that happen.

Was never a big fan of the open top Colt revolvers. Had a couple at various times. My first hand gun was an Italian replica Colt Walker kit back in the day. And only my second gun build as well. First was a muzzle loader rifle.

Old Man in Al:

Regarding “chain fire:”

Personally, I’ve never fired a cap-and-ball revolver in my life. However, I’ve heard it said that the shooter should apply grease to the caps after insertion on the nipples to dampen any escaping hot gas, which could otherwise cause a chain fire incident. Above, possum says that he has used candle wax to waterproof the caps, which practice (I suppose) would accomplish the same thing.

I don’t know what I wrote here, which caused me to be moderated. Will the TTAG powers-that-be please enlighten me???

Comments are closed.