The Billinghurst-Requa battery gun is an unusual piece of armament that resulted from an equally unusual partnership between two men from New York: William Billinghurst, a gunsmith, and Josephus Requa, a dentist.

Before Josephus Requa settled on a profession, he spent three years as an apprentice to William Billinghurst learning how to make and repair firearms. After his apprenticeship ended, Requa decided on a different professional direction. He began his study of dentistry in 1853 and was in practice for himself by 1855.

Despite their different vocations, Requa and Billinghurst remained friends through the years. When Requa answered the military’s call for a rapid-fire gun in June 1861, he came up with a design and then consulted with Billinghurst on its feasibility. They built a scale model within the next two weeks and then proceeded to create a fully-functioning prototype soon thereafter.

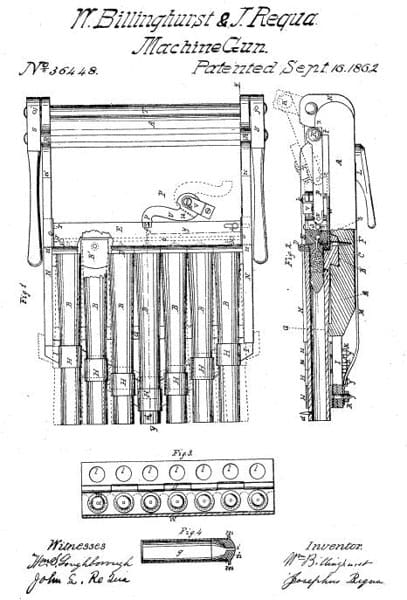

The design for the Billinghurst-Requa battery gun included 25 barrels mounted horizontally to a wheeled carriage. A clip of 25, .52-caliber metallic cartridges were loaded in front of a bar at the breech of the barrels. When the attached lever was manipulated, the cartridges were pushed forward into the barrels and the hammer on the single percussion cone was cocked.

Once the breech was closed, a line of blackpowder was placed in a trough behind the cartridges, which had small holes in their bases through which to channel the powder ignition. A percussion cap was placed on the cone, a lanyard was attached to a trigger, and then one person could pull the lanyard and fire all 25 barrels at once.

Because the cartridges were held together by a clip, all 25 could be removed at once, allowing for faster reloading. A crew of three men could fire the gun up to seven times per minute, creating a rate of fire of 175 rounds per minute.

In April 1862, Requa met with Brigadier General James Ripley, head of the Ordnance Department for the United States Army. Ripley, believe it or not, is best known to history for his refusal to implement shoulder-fired repeating firearms in combat, citing their faster rate of fire to be a waste of ammunition. Unfortunately, he had the same view of the Requa-Billinghurst battery gun as he did of the Henry repeating rifle.

Despite being rebuffed by Ripley, Requa met with President Abraham Lincoln in May 1862. During their meeting, Requa explained the gun’s function and Ripley’s dismissal of it. Lincoln gave Requa a note to give back to Ripley, basically telling him to listen to Requa. Even so, Ripley was unmoved by Lincoln’s note, so Requa went back to the President and finally arranged for Lincoln to see the gun in action.

Two demonstrations in May proved successful and a patent followed on September 16, 1862. Still, Brigadier General Ripley dug in his heels; no government contract would ever materialize as long as Ripley had anything to say about it.

Despite not having the official blessing of the United States Army, Billinghurst-Requa battery guns did see service during the Civil War, albeit on a small scale. Fifty guns were produced with money raised from private backers. The 18th New York Independent Battery purchased a couple of those examples and used them in combat down in Louisiana. The battery guns were seen by Major General Quincy Gillmore, who ordered enough guns to outfit five batteries to aid in the capture of Fort Wagner on Morris Island, South Carolina in 1863.

The government’s final test of the gun came in August 1864. Even though the gun proved to be reliable and useful, military procurement being what it is, it took two years for the final report to give that official determination. At that time, Billinghurst and Requa finally received their one and only government contract…for five guns, a year after the Civil War had ended. It would prove to be too little, too late.

The two men never designed another weapon together and faded into relative obscurity. The final public display of their battery gun, now simply a novelty, was done at the Pan-American Exposition in 1901.

Logan Metesh is a firearms historian and consultant who runs High Caliber History LLC. Click here for a free 3-page download with tips about caring for your antique and collectible firearms.

It figures that William Billinghurst, a gunsmith, and Josephus Requa, a dentist, would build a military weapon.

One of them was steeped in blood and gore with no feeling whatsoever for human suffering and the other was a gunsmith.

Reckon you would not be of kind disposition regarding Dr. Richard Jordan Gatling.

What is the with dentists and multi-barreled guns?

What amazes me if the incredible differences of technology leaps made between the beginning of the US civil war and World War One. That’s not that long of a time. For reference, that’s the difference between Vietnam and now. 1860, armies were armed with primarily rifled muskets, muzzle loaded smooth bore cannon and ships were made of wood. 50 years later, Airplanes, air ships, battle ships, submarines, machine guns, bolt rifles and sub guns, poison gas, and tanks. That is quite a leap.

The industrial revolution. The ability to mass produce, more advanced designs along with improvements in metallurgy and chemistry. New machining techniques and technology would speed up prototyping. Also the R&D from engine designs and mechanics probably helped advance machine gun development.

What amazes me about the Civil War is the level of accomplishment by soldiers, officers, logisticians, and what would become combat engineers in later wars. They did it all without radios, telephones, fax machines or powered earth-moving equipment. Imagine the difficulty of controlling and coordinating a combat patrol (platoon size) in the Sandbox without electronic communication. Imagine that same condition raised to division and corps level.

Carrier pidgins…

Anticipating the multi-barrelled mortars and rocket launchers in WW2 known as Hedgehogs.

I think the Chinese had something more related to multi-rocket launchers in the 900s:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vO6I5OZpRDI

(skip to about 2:00)

The Koreans had a rocket-powered arrow launcher too, similar to an MLRS on a smaller scale.

Cool. I love articles like this.

Me too. The historical articles don’t draw many comments, but they’re some of the most interesting and worthwhile reading on this website.

“Ripley, believe it or not” lol was I the only one that caught that?

Also on an unrelated note Ripley sounds like a super fud that hates cool things.

Some commanders like to think that regardless of equipment or quality of troops, their genius is what wins battles (some are even right), Ripley, as a general officer may have had a bit of that in him, even if he never commanded a fighting force. What’s more likely though (and I’ll admit this is pure speculation, as I know very little of Ripley), is that Ripley didn’t trust the average soldier to pick up the nuances of the weapons operation and maintenance, or the average officer to employ it correctly, thus making the weapon an extravagant liability on the field and a logistical nightmare that could end up reflecting badly on him. Then again, perhaps he really was just that unimaginative. Now I’m suddenly craving a good biography of Ripley…

I recommend the book ‘American Rifle; A Biography’ by Alexander Rose. There’s quite a bit of info on Ripley, a man who was universally disliked, stuck rigidly to the rulebook, refused to countenance newfangled tech (repeaters etc) but basically whipped the ordnance department into shape. He was responsible for the efficient mass production of arms required to provide every soldier with a rifle but had to be dragged kicking and screaming into the breech loading age!

The Ripley sentence brought a smile.

The Ordnance Dept was skeptical of rapid fire rifles up to modern times, supporting only the squad auto rifle (like the BAR) and descendants. Same argument…wastes ammunition. Was the department wrong? A news story from the Vietnam era is instructive. The article discussed American combat patrol experience compared to the experience of the Aussies. Aussies put a patrol together to remain in the bush for 30 days. Ammo load-out was 100rds per rifleman; no resupply. Americans carried what seemed to be inexhaustible amounts of ammo for about a week. Americans were very fond of suppressive fire, a virtual wall of lead, when engaging the enemy. If you find some of the TV footage from the ’68 Tet Offensive, you will see US soldiers rapid firing and reloading M-16 rifles, with the rifles held over the head, protruding from the embassy wall; shooting blind.

“If you find some of the TV footage from the ’68 Tet Offensive, you will see US soldiers rapid firing and reloading M-16 rifles, with the rifles held over the head, protruding from the embassy wall; shooting blind.”

I’m not sure of how widespread that was, but at the very least in that case it says volumes about the lack of training and leadership the troops had.

Mention of this “Battery Gun” was made in some TV Show on the History Channel. At the time I saw it I thought that a Standard Napoleon Cannon of the time loaded with Canister Shot would be about as effective, so maybe that’s what Ripley thought, as well. There were other “Volley” guns, but most of them required laborious barrel-by-barrel muzzle loading and had notorious challenges with ignition. So, the Billinghurst-Requa design was possibly a vast improvement, albeit on a dubious concept.

The American Civil War (or the war of Northern aggression for you Southerners) was the first modern war

Trench warfare, massed artillery barrage, ariel observation (from balloons), rapid mechanized troop movement ( by train), repeating rifles (Spencers), and machine guns (Gatling guns). were all used

The First World War was the same, only bigger with the addition of poison gas

Modernity has always been a movable feast. Entrenching around siege targets such as fortresses or cities was common from medieval times and before. Entrenching as a defensive move on the actual battlefield is more recent. One of the earliest examples was the musket wars of the 1840s in New Zealand, where Maori skill in trench works was almost able to overcome superior British firepower. This was reinforced with the Maori Wars of the 1860s (mostly the British using one Maori tribe against another, with colonial and British troops from India adding force), where the level of Maori fortification and trenchworks astounded British officers. The Crimean War also added expertise. But the advances in breechloading rifles, repeating rifles and later machine guns and artillery, outpaced military tactics at the senior officer level, hence the huge losses in the Civil War in the USA, and later in World War One.

Comments are closed.